Can survival games tell compelling stories, and why do they bother?

Survival games like Subnautica, The Forest, and The Long Dark have top-down, writer-led stories, but it’s a genre where players can just as easily tell their own ground-up stories by setting their own goals. As Tanya X. Short, captain of Kitfox Games (publisher of the Steam edition of Dwarf Fortress (opens in new tab)) puts it, “The traditional capital-s ‘Story’ is the authored kind, right? The designers are trying to have this plot or these events happen to tell their traditional narrative, but the player story often eclipses that.”

Tanya X. Short, Raphael van Lierop, and Giada Zavarise will be among the panelists discussing “Survival Story-telling” at LudoNarraCon (opens in new tab), an online festival about narrative in games that runs from May 4–8 this year.

It took Chris Livingston four hours and the lives of 12 poor sheep before he got his toilet working. I should clarify this was while he was playing Ark: Survival Evolved, he’s not a mediocre plumber with a lamb chop addiction in real life. Chris set off on his quest for a crapper when Ark gained interactive toilets in update v258. He came out of it with a functioning fartbox, but more importantly, an unforgettable story—one he wouldn’t have in a game that didn’t simulate the need to eat and excrete.

It’s true that survival games are fertile ground for player-led stories. Everyone who plays DayZ comes out with a harrowing tale about a tense stand-off with strangers, and everyone who plays Valheim has their own Viking saga (even if it ends with a tree falling on them). These pub anecdotes may not be equally thrilling, but they’re ours.

“People telling you stories about their gameplay, their experiences in Valheim or in PUBG or whatever, it’s a lot like having someone describe the events of a dream,” says Short. “They’re not necessarily meaningful to the listener… but extremely distinctive and memorable to the person who was involved in it.”

Short is no exception. When she started playing Dwarf Fortress, she immediately wanted to tell everyone what happened. “I was like, ‘The elk birds are running amok in my fortress! And the dogs keep chasing them! And it’s been 10 years! How is this still a thing?’ I think that’s a fairly normal occurrence, but to me it was special and that’s my story of my fortress. But then occasionally you’ll get the mermaid farms.”

The mermaid farms are infamous among Dwarf Fortress players, and they came about as a natural consequence of players considering the simulation. Dwarf bone carvers can make totems out of skulls, and the totem’s value is based on the bones used to make them. Merpeople had valuable bones. Theoretically, it would be worth harvesting them. The mermaid-farming forum thread (opens in new tab) began by suggesting a mechanism involving a double-floodgate trap corridor, and continued until players were debating the merits of building catapults to fling merbabies into walls as the fastest way to separate their skeletons. (A subsequent update devalued their bones, ending the threat of merpeople genocide.)

Not every survival game is a pure sandbox of player-driven chaos, of course. The Long Dark keeps its episodic story campaign a separate mode from the sandbox. “It was a decision originally made for development expediency,” says Raphael van Lierop, The Long Dark’s creator, writer, and director, “but over time it’s become core to how we approach development of the game, allowing us to update each part individually, and also let each mode breathe and evolve along lines that feel most organic to its nature. A successful authored survival story needs different things than one where the narrative is authored purely through systems and player choice.”

The tension between surviving and storytelling

The Long Dark tosses you to the wind in a Canadian wilderness where the bears and wolves compete with hunger, thirst, fatigue, and the cold to see who’ll kill you first. As van Lierop says, “when I play a game that doesn’t have survival mechanics, I feel like something is missing.”

It’s very easy for the player to start fixating on the optimal strategy and the optimal strategy is likely to not be super fun.

Tanya X. Short

The rudimentary wildlife simulation of Skyrim—wolves chasing deer, foxes chasing rabbits, fur that can be crafted into leather and meat into meals—seems to beg for them. Mods like Frostfall (opens in new tab) and Campfire (opens in new tab) give you reason to eat apple cabbage stew even when you don’t need the hit points, as well as making blizzards as dangerous as the ones in The Long Dark.

For a while those mods were an essential part of my load order, but these days I leave them out. When I’m doing quests all that stuff becomes another distraction in a game that’s already got plenty.

“A lot of open-world games struggle with the disconnect between narrative intensity and momentum, ‘You have to go here and quickly!’, against this big world full of interesting things to do,” says van Lierop, “and you have to be able to do them but also feel that sense of urgency once you re-engage with the narrative. It’s even worse in a game like The Long Dark because your survival needs introduce their own tensions that can’t be ignored.”

I’ve certainly had moments of that. In The Long Dark’s story mode, while near death and exhausted, I wandered into a house looking for somewhere to sleep and instead found an important NPC. One story-critical dialogue scene later I turned to leave, but by then was on the point of delirium and lost control of my movement, stumbling around like a maniac while I tried to reach the door. I died before I managed it.

“Not only do we have to bulletproof our in-game narrative scenes to work regardless of what time of day, or weather, or whatever else might be going on that could interfere with your beautifully paced dialogue,” van Lierop says, “but we have to write around the fact that at any point, our player might be near death for any number of reasons.”

The mechanics can become a part of the narrative if you think about how it’s all tied together

Giada Zavarise

Giada Zavarise, a narrative designer, writer, and noted hater of fishing minigames (opens in new tab), believes there are simply limits to the kind of stories survival games can tell. “You can’t make stories or quests or whatever that are actually too long,” she says, “because then the player will be in the middle, like, ‘Oh, I’m actually hungry, I need to go back.'”

What keeps mankind alive?

The way to deal with that, she says, is to follow the example of Delicious in Dungeon, a manga where broke adventurers turn their enemies into nutritious meals. “I think that it’s best when getting the resources is actually part of the story.” Make obtaining meat the meat of the story, essentially. “That is a manga that would work very well as a game because you can tell that the artists thought about all the stupid things you can do in D&D,” Zavarise says, but until we get a Delicious in Dungeon videogame, which I agree would be excellent, others will have to lead the way. Zavarise mentions Miasmata, a game about searching a mysterious island for the cure to a disease you’re suffering from, as an example.

“The mechanics can become a part of the narrative if you think about how it’s all tied together,” she says. “In Miasmata, the main focus is not just on getting food and sleep, it’s also getting the medication, and if you don’t do that your vision gets wobbly.” Meanwhile, there’s a creature stalking you through the undergrowth, always on the periphery. Maybe that was a movement in the bushes, or maybe it was just a symptom of your deteriorating condition. “I think that narrative was very compelling because it was like, ‘Is the monster an illusion, is it a real monster?'”

In Miasmata, being bad at survival enhances the story’s impact. But as well as the risk survival games run of players being distracted from quests by a hunger bar running low, there’s a risk at the opposite end of the success spectrum. “The main danger of a sandbox is when someone chooses to do something they don’t enjoy,” says Short. “That’s a very tempting thing if you have any traditional game elements in there, if you have any sense of progression, or ‘number go up’, or scarcity. It’s very easy for the player to start fixating on the optimal strategy and the optimal strategy is likely to not be super fun.” She thinks about this for a second. “Unless you’ve made Factorio,” she adds.

When you’ve played a survival game long enough to find a safe and efficient resource-gathering loop, there’s a temptation to just keep doing that forever. “The tricky thing is not letting people fall into a rut of what they would call grinding,” Short says. “Because as soon as they’re there, a non-dangerous, non-risky, non-emotionally invested set of activities over a long period of time, that’s naturally going to defuse any kind of dramatic tension.”

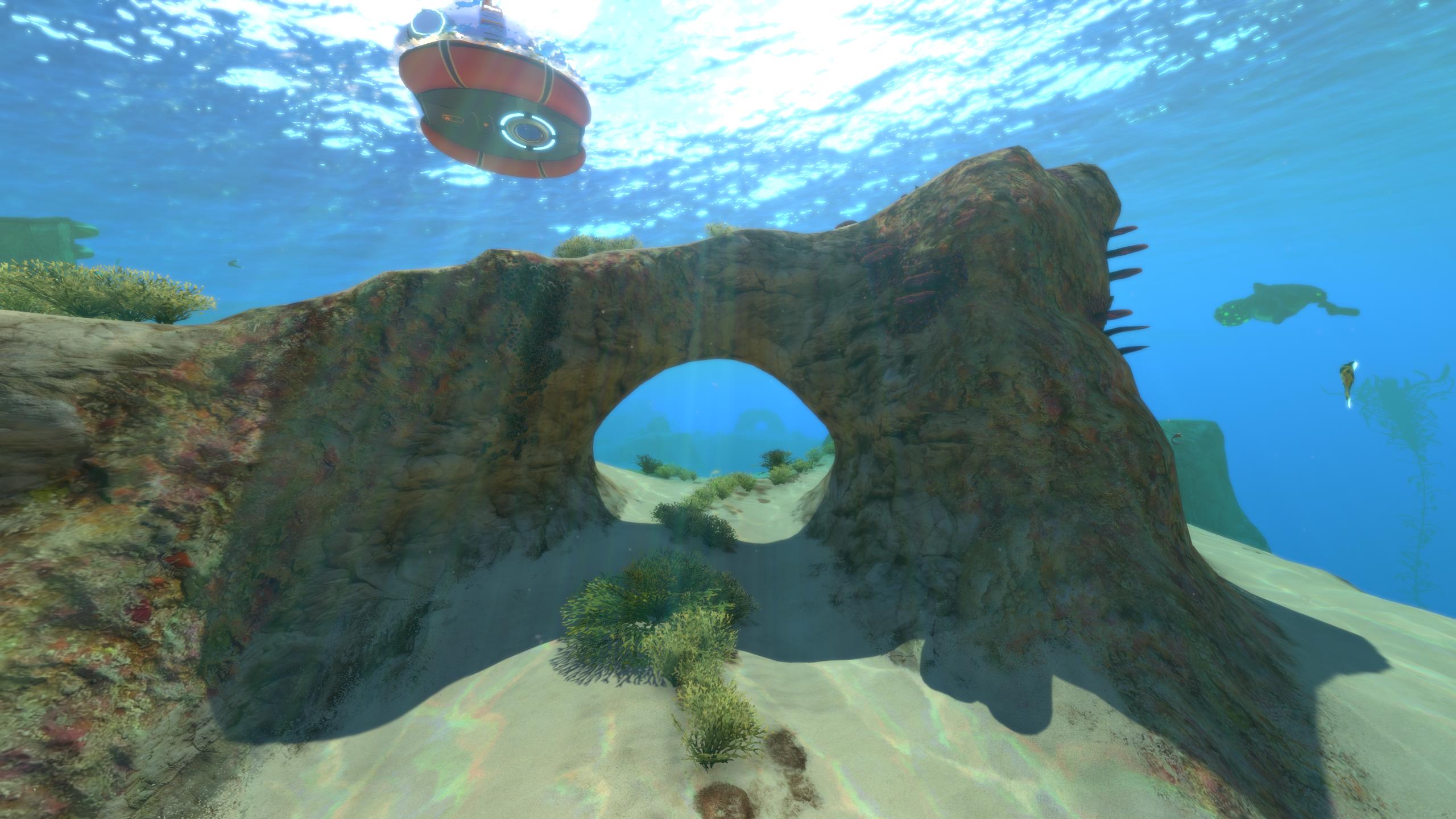

Zavarise says the descent into risk-free repetition is why she thinks of survival games as “mostly self-care games”. Sure, you may have urgent needs, but you also have the skills to fulfill them. “You can have the fantasy of actually taking care of yourself,” she says. “A lot of games, like Subnautica, you start that in the middle of the ocean and you only have this small capsule, but then you have a lot of base-building. So it’s the fantasy of not only surviving, but also thriving—having your own house without having to pay rent.”

I would just like to see different environments

Giada Zavarise

In the times when I’ve grown too comfortable, when I’ve got a day-to-day schedule and a base that’s defensible, whether or not it has a working toilet, it’s always been a desire to see the story that’s pushed me on. I leave my cozy hole, building a Prawn suit to explore the depths in Subnautica or jumping through a portal into adventure mode in Don’t Starve, because I need to understand what’s really going on. Purely sandbox survival games get boring after you’ve made a home for yourself, but that’s where survival games with stories can come into their own. It’s because we’re curious about what will happen next that players summon the next dangerous boss in Valheim, or walk back out in the snow to find Jennifer Hale in The Long Dark.

“Getting the player to care enough to engage, to follow, to be led in some cases, and to drive themselves forward to pick up the breadcrumbs you’ve left for them—it’s very tough,” says van Lierop. “We’re still learning how to do it well.”

What’s it all about, man?

The survival games discussed so far are mostly the kind where you, and maybe your friends, chop down trees and catch fish. You build shelter, you try not to get eaten. They’re elemental stories of life and death. “From the first moment you already have the highest possible stakes,” says Short, “like, death is right there. OK, now how do you move up? How do you increase drama?”

“I think that most survival games are still figuring out the basic foundations of how to make things like crafting, resource management, exploration, etc. intriguing,” says van Lierop, “but nobody is really tackling the deeper themes and issues around what it means to survive. So I think we’re just scratching the surface of what stories, and experiences, can be expressed through these mechanics. There’s a long way to go, yet.”

Zavarise suggests changing the default setting would broaden the available themes. “I would just like to see different environments, like my GDC Simulator,” she says, referencing an early game of her own, “a survival game about a game dev convention, so your resources were, snacks, business cards, your stress level, and you could just decide to go back to your hotel room because you are too overwhelmed by people.” She’s in favor of “games that are not just set on a desert island again, games that are about surviving maybe an urban environment.”

Another way to change the stakes is to change the scale. Normally we think of survival games being about individuals who strive against nature like Bear Grylls or a Hemingway hero (Raft is just The Old Man and the Sea with multiplayer). If we broaden our definition to include games like Frostpunk, the kind of settlement builders and management sims where you’re in charge of a community rather than individuals, the possibilities open up.

“The Six Ages (opens in new tab) and King of Dragon Pass sort of paradigm,” Short calls this. “You’re helping your clan survive and it’s very clear that your clan definitely can disband if you make a few bad choices. Extending up from there in that way it’s easy to think of even Paradox games as survival-y.”

No matter how much care we put into our storytelling, we’ll never come up with anything that players care about as much as their own stories.

Raphael van Lierop

In Frostpunk, the equivalent of the anecdote every DayZ player has about being held at gunpoint by strangers is the story of when you decided to institute child labor. Look, someone has to drag that coal to the furnace, and when every available adult is either hospitalized or working in the hospital, it’s time to send in the kids. Frostpunk stories are about life and death, but they’re also about what sacrifices are worth making to keep life worth living, balancing order and compassion, hope and despair.

“In Dwarf Fortress, the kinds of things you pay attention to in the early game are very different than the kinds of things you pay attention to 10 hours, 100 hours later,” Short says. The difficulty is having the mechanical detail to simulate a community, whether a mine full of dwarves, a clan of barbarians, or a city of frozen Victorians who care about how they live as well as whether they survive. “You have to have the kinds of systems that can continue to deepen after 10 hours, 100 hours. Like, hunger can’t be that complicated.”

No matter how hard survival games work to make us care about their stories, there’s always the likelihood players will come away remembering their own instead, whether it was about farming mermaids or building a single toilet. The developers I spoke to are all pretty serene about that.

“It’s more personal,” says Short. “In all games of course the player story often becomes the focus, but especially in more systemic games.”

“We set the stage,” van Lierop says, “we create an engine for extreme serendipity or colossal disaster, and the player brings meaning to it all. Even better, they feel full ownership for their journey. No matter how much care we put into our storytelling, we’ll never come up with anything that players care about as much as their own stories. And isn’t that really the strength of this medium to begin with?”