I’ve seen Nvidia’s G-Sync Pulsar in action and it’s kinda ruined all other gaming monitors for me

There are certain things in life that, once seen, can’t be unseen. The arrow in the FedEx logo, for instance. Or the fact that my beard is rapidly going grey, proving once and for all that I am truly a mortal man.

Well, I’ve had a chance to check out Nvidia’s new G-Sync Pulsar tech in action at CES 2026, and now I’m afraid that all other gaming monitors look a bit… crap. It’s Medusa-like tech. I’ve seen it, I can’t unsee it, and now I’m forever changed.

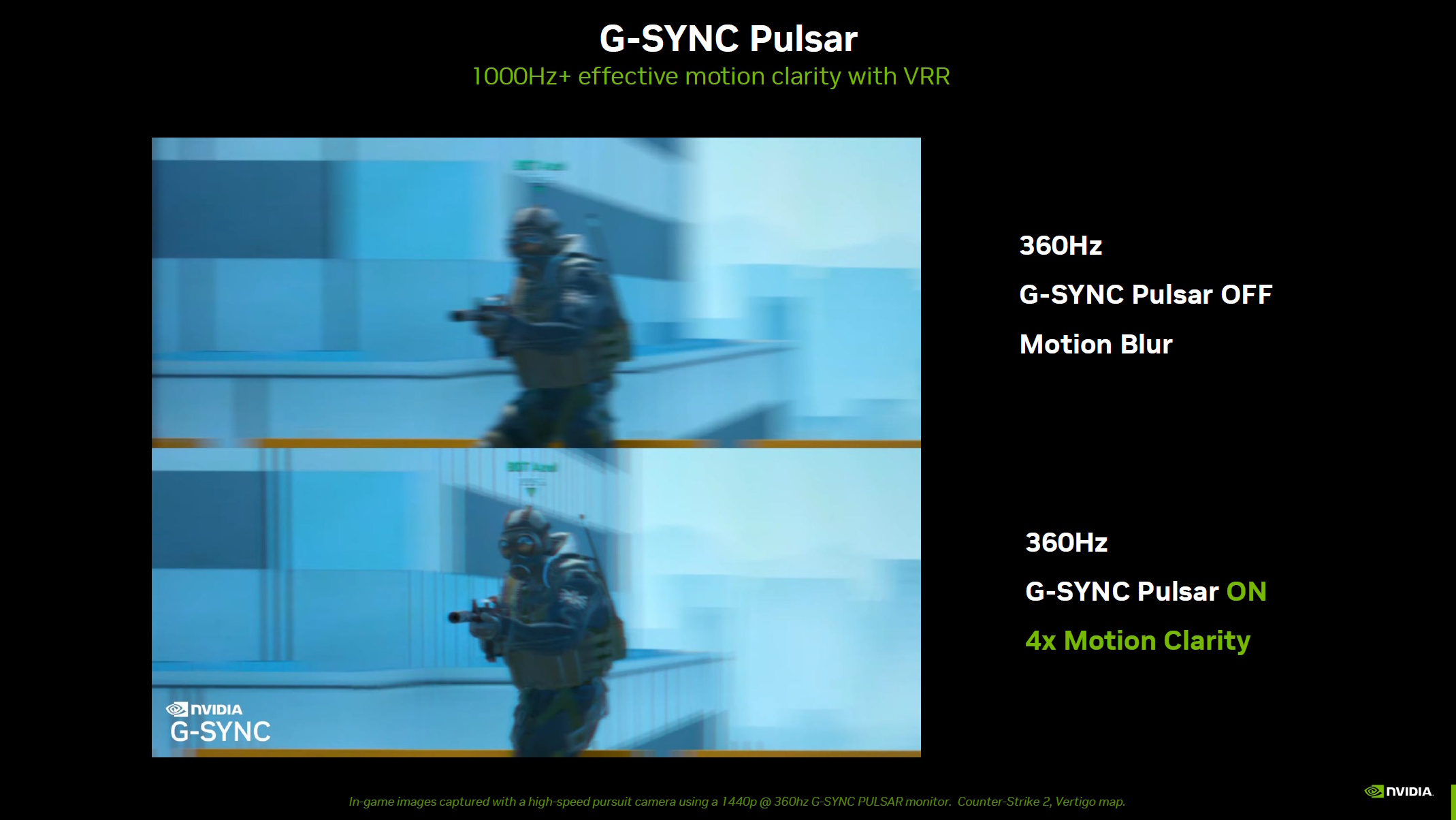

Suddenly, it felt like my eyes were no longer struggling to keep up with the fast-moving image. The picture overall, with both fast-moving and static objects, seemed to beam straight into my retinas with impressive precision—resulting in a moving image quality that looks miles ahead of anything I’ve seen to date.

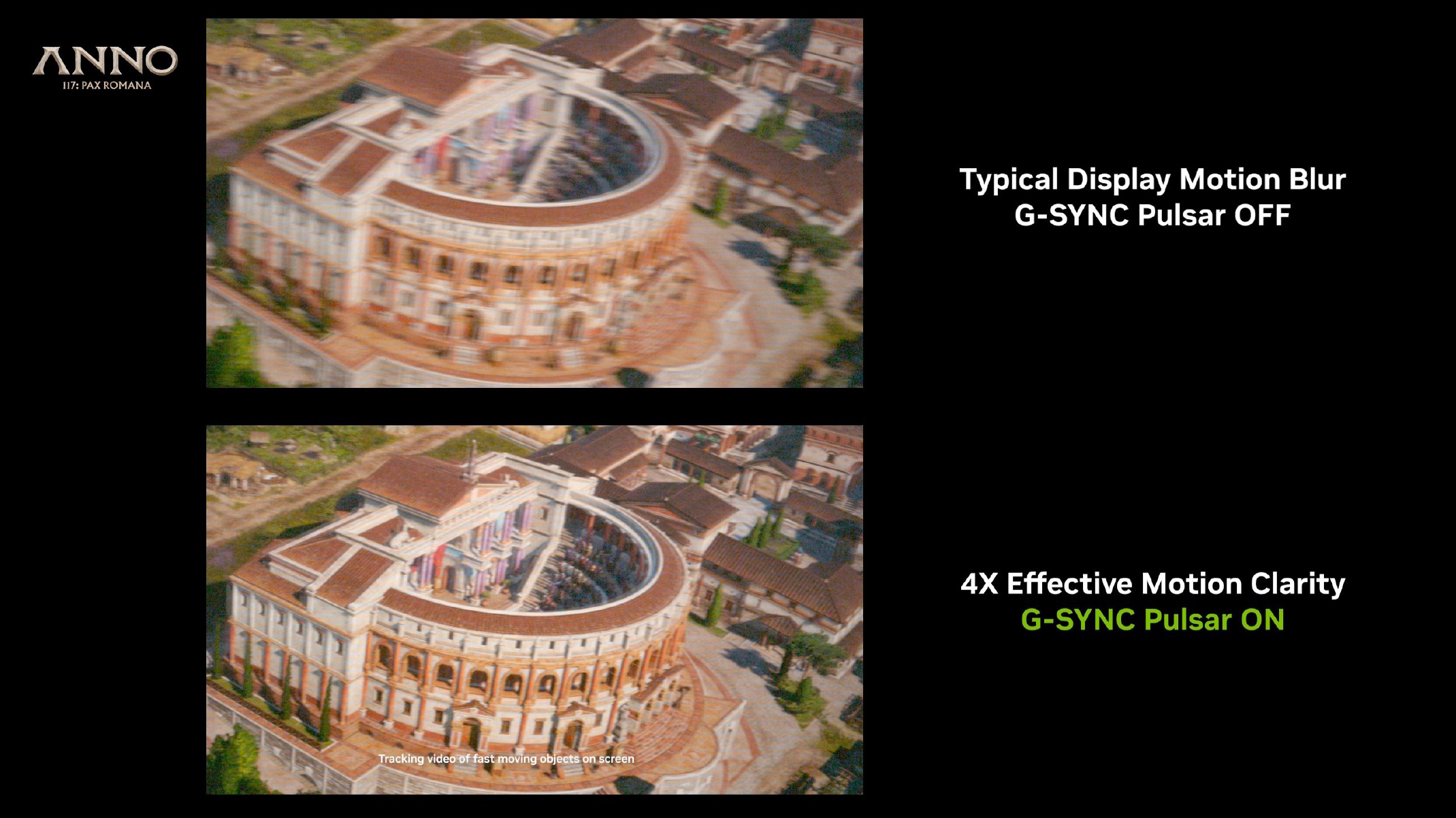

I was also shown a demo of Anno 117: Pax Romana running on the monitor tech, which initially struck me as an odd choice. After all, city builders aren’t exactly known for their fast-paced action. However, moving the camera around instantly revealed why Nvidia picked it as a demonstration piece. Tons of icons, overlaid on a detailed map, with lots of zooming in and out of the game area.

Again, the clarity difference under motion was undeniable. One was hard to parse under fast movement, the other, completely legible, whether focussing on details or looking at a moving scene overall.

Now, you’re going to have to take my word for this (and some less-than-useful still images), as capturing the effect in person is a nigh-on impossible task. Camera sensors, conflicting frame rates, video compression, it all take its toll. Capturing new monitor tech advances on an average lens is akin to describing your favourite movie through the medium of interpretive dance.

But let me tell you, as someone who’s stood in front of hundreds (likely thousands, at this point) of extremely good gaming monitors, the way G-Sync Pulsar changes how you perceive fast moving images is downright profound.

Chatting to Lars Weinand, one of Nvidia’s senior technical project managers, about the tech revealed a bit more about how it works:

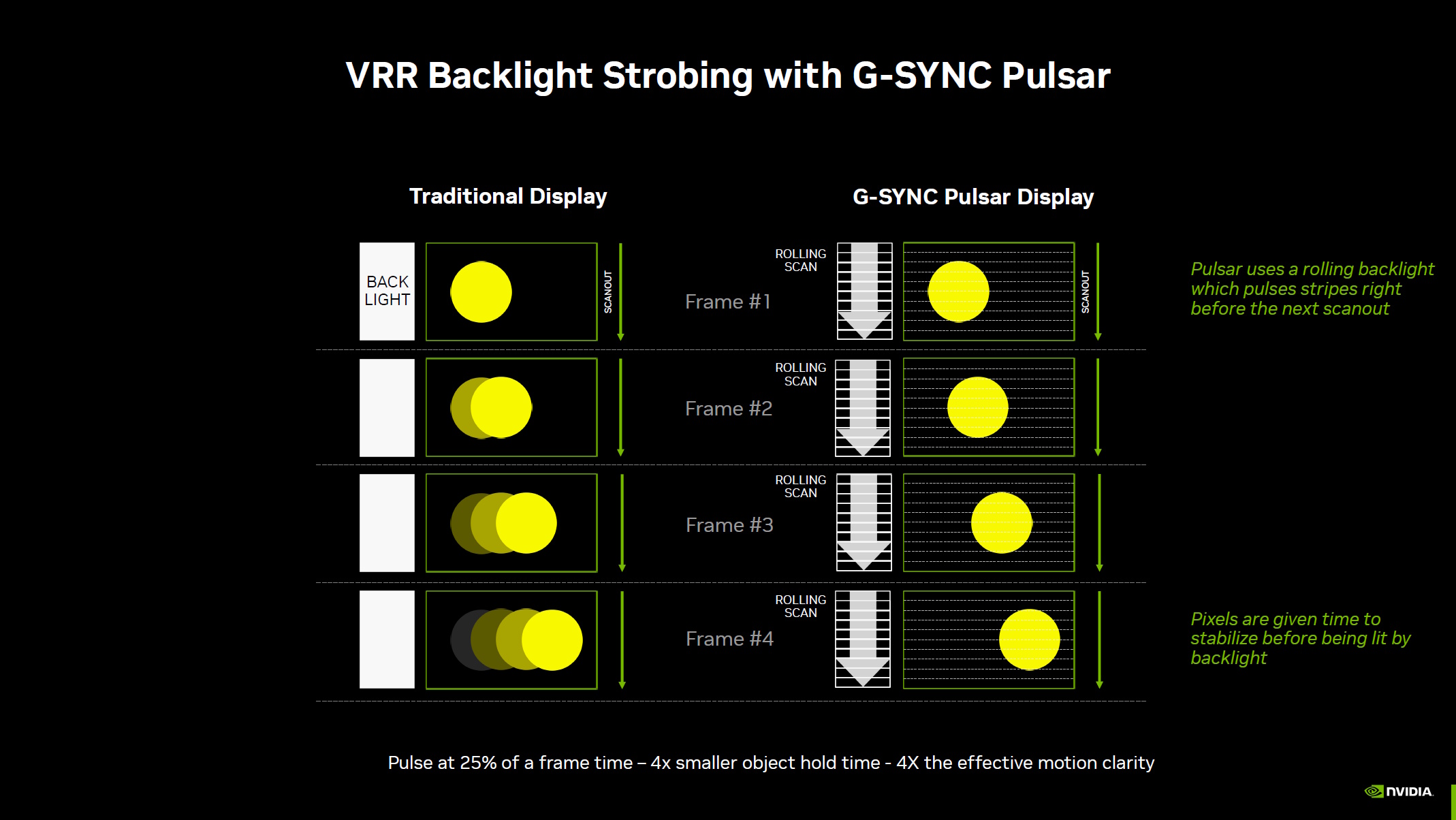

“There’s a problem called motion hold,” Weinand explained. “When the backlight is on, and the pixels are always visible, the screen is drawn from top to bottom for every frame—meaning that when there’s movement, the pixel is drawn, and then it stays in position for a whole frame until it’s overwritten by the next one.

“In the way our retina, our human system works, our brain interprets this as motion—when I move my finger like this (Weinand moved his finger quickly in front of his eyes at this point), it’s blurred, right? That’s how our vision system works.”

“So what we do to avoid this, with an LCD, we turn off the backlight and only show [the frame] once it’s settled in position. In the previous version, this always strobed the whole screen at once. So that was ULMB, but it never worked with VRR.

“What we’re doing now is a rolling scan, so the scan out is happening from top to bottom, and we strobe right before the scan out reaches the next section [of the display]. This way, we can make it variable, because at a different refresh rate, if that changes, the stroke needs to go faster.

…the end result is that you get four times higher motion clarity

Lars Weinand, Nvidia

“So the display is handling all that, adjusting to [refresh rate] frequencies, adjusting the strobe, and the end result is that you get four times higher motion clarity.”

Combining the strobing technology with the silky smoothness of VRR really does appear to have made a massive difference to the overall effect. I saw a previous iteration of the tech many moons ago when it was still under wraps, and I was impressed then. Now? It feels like a genuine game changer.

CES 2026

Catch up with CES 2026: We’re on the ground in sunny Las Vegas covering all the latest announcements from some of the biggest names in tech, including Nvidia, AMD, Intel, Asus, Razer, MSI and more.

There are downsides, of course. Not all panels are G-Sync Pulsar capable, as it requires fast-responding IPS backlights that need to be approved by Nvidia as capable of delivering the effect. Plus, it requires an onboard MediaTek scaler chip, and the method doesn’t work with OLED displays, which light each pixel individually rather than using a backlight.

And while a variety of G-Sync Pulsar displays will be available from January 6, the cheapest variant in the first batch is an AOC model with what I’m told will likely be a $600+ price tag—which is a lot to pay for a 27-inch 1440p IPS panel.

Still, having seen G-Sync Pulsar in action, I’m thoroughly convinced by the uplift in perceived motion quality. The thorny question now is, which would I rather have—the incredible contrast and vivid colours of a brilliant OLED gaming monitor, or a pin-sharp, ultra clear, fast-responding IPS for similar cash?

In all honesty, I might still plump for the OLED. But now I’ve seen G-Sync Pulsar in person, it’s more of a close-run thing than you might think.