After being inspired by Toby Fox to make his first RPG in decades, cult developer Yoshiro Kimura couldn’t help but make it weird: ‘Some people are going to look at it and go that’s kind of odd, but that’s just the way my games turn out’

Yoshiro Kimura seems to only be half kidding when he tells me that he “escaped” from Squaresoft in the mid 1990s, where he’d started his career as a game designer on Romancing SaGa 2 for the Super Nintendo. Even back then, when game studios were a fraction of the size of today’s behemoths making Call of Duty or Assassin’s Creed, he wanted to work with a smaller team, where his own ideas could shine through.

“Making games, money aside, it’s fun, and it needs to be fun to make something fun,” he told me over coffee in Tokyo in late September. “With a smaller group of people, you’ve got all the essential elements to make a game, and they’ve all got their own special abilities. One is great at art, another is great at programming. And to share the vision, it’s a lot less work.”

That remaster—and now Stray Children—both partially exist thanks to an enthusiastic member of Kimura’s cult following: Toby Fox.

Watch On

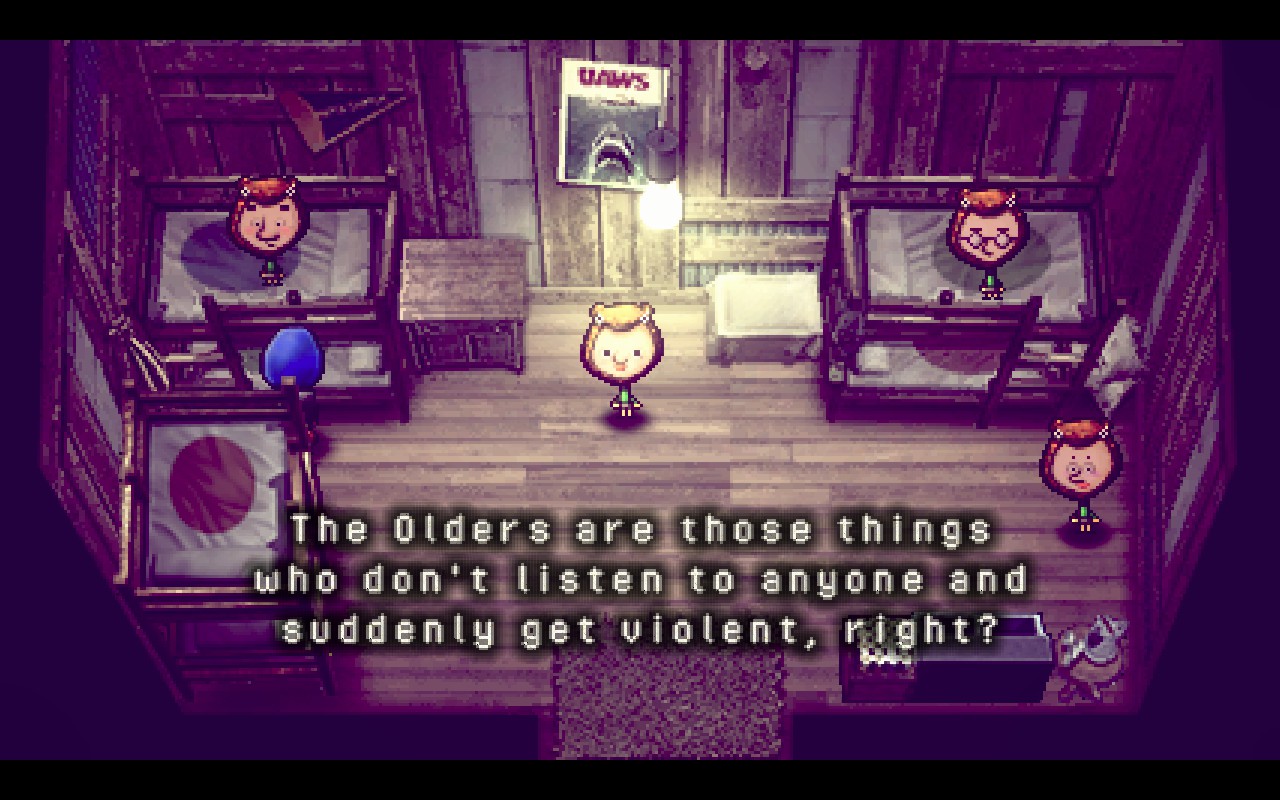

Kimura became friends with the younger developer after Fox told him that Moon had inspired Undertale. Stray Children, in turn, takes a page from Undertale’s puzzly pacifism combat: in battles against monstrous “Olders,” your child protagonist can quickly kill them with attacks or much more laboriously heal them by whispering the correct sequence of encouraging words into their ear.

“I think Toby and myself have one thing in common, which is that we both really like odd, weird, bizarre games. … When I’m making my games, Stray Children included, it’s like a love letter to other people in the world out there who love these odd games, like Toby and I do.”

I asked Kimura if he thinks of his own games as strange. In Moon, instead of going around fighting monsters with a traditional RPG battle system, you essentially solve puzzles to save their souls. Stray Children begins with you being sucked into a virtual game world, a common trope—but within minutes that world crumbles to digital dust, sending you a layer deeper into unreality.

“For me, the games I make and how they turn out, it’s second nature,” he said. “And I think they’re fine. But I also realize that they’re probably not for everyone. … Some people are going to look at it and go ‘that’s kind of odd.’ But that’s just the way my games turn out.”

The way Onion Games’ team of seven made Stray Children is itself unusual.

“Until the game is done, the only person who knows what’s happening is me. Nobody knows how all [the scenes] fit together because there’s no documentation for that, except in here,” he said, tapping his temple. That only works because they trust each other. It also means that near the end of development, when they finally put the pieces together, he can see how everyone on the team digests the story’s twists and make adjustments based on their fresh reactions.

While Moon seemed like an obvious response to the traditional RPG, Kimura said that the themes for all of his games now stem from day-to-day life. “I find myself concerned that we as adults are getting in the way of the younger generation, children’s futures,” he said. “I’m conscious of that myself and try not to be that kind of adult. At the same time, children are often thought of as pure; they’re good, not evil. But are they really? Is everything really that black and white?”

The first kids you encounter in Stray Children, dressed in animal costumes and living in a vaguely Lord of the Flies-style commune, suggest it’s not.

The game’s combat, which clearly borrows from Undertale’s pacifism route, is the sort of trial-and-error frustration that makes you question whether it’s bad design or winking commentary on classic turn-based RPGs or the relationship between the young and old. So far it’s the exact sort of divisive mechanic you’d expect from a cult classic in the making—perhaps more interesting to discuss and ponder than to actually play.

“Every action you take results in a long, long, LONG attack pattern that is just a nuissance, even if you’re doing things correctly… I want to keep playing it because I’m interested in seeing what happens, but jesus christ, for your own sanity, watch someone else play it,” says one Steam reviewer.

“I’m just a bit in but this is already as potent as you can make art in this medium,” says another.

RPG Site writer Cullen Black cut to the heart of this tension in his review. “You receive experience however you decide to deal with a foe, but making the choice to play the game harder in exchange for a moral victory without violence has its benefits… This is where Stray Children’s heart lies. In a story about stagnating adults chewing up and spitting out children who just don’t know any better. It’s all filtered through this dream world you find yourself in, and it’s up to you to choose if these harmful people deserve to work through their problems or not. That trial-and-error nature of combat, as much as I think it was designed unevenly, does convey that dilemma throughout the entire game…

“Stray Children is basically everything I wanted from a successor to Moon. The friction I crave from that kind of game is here in full force, not even bothered with the idea that it might scare away any prospective players.”

Without Toby Fox there may be no Stray Children, but Kimura credits indie games, in general, for inspiring him to keep creating, even as the audience for his games has remained small. But these days he’s more optimistic than he once was.

In the early 2010s, Kimura was depressed because of the popularity of Facebook games and the Japanese gaming industry’s hard shift towards free-to-play on mobile. Maybe there just wasn’t an audience for the kinds of games I make, he thought at the time. Then he visited the Game Developer’s Conference in San Francisco and wandered through the Independent Games Festival’s showcase.

“I saw this huge variety of games made by a huge variety of people from all walks of life, all these screens in front of me, and I found myself in tears,” he said. “Why was this happening? Why was I feeling like this? The conclusion I drew: if you were on a safari in Africa or climbing a mountain and seeing this great expanse of nature before you, and you’re moved to tears. Maybe it’s like that: Making indie games is like a living thing, like the Earth itself. An ecosystem…

“Making games is not an easy thing. But facing these challenges is one of life’s pleasures.”