Tech CEOs don’t seem to realise just how anti-human their AI fanaticism is, and I think it’s all because of the Enlightenment

Jacob Fox, hardware writer

This week: I’ve been playing a lot of Killing Floor 3, plus trying out a new laptop and fiddling with the cable management around my desk.

Last week I watched Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang and AMD CEO Dr. Lisa Su take to the stage at the ‘Winning the AI Race’ summit and talk about how great AI is. That much was expected. But as I listened, I realised the cat is finally out of the bag: The anti-human drive that underlies much (but not all) of AI fanaticism is no longer being hidden quite so ardently.

First, I heard Su’s comments that, to prepare the future generation for AI, we should “revitalise” the curriculum for kids’ education to give a heavier leaning towards science and technology. At least, that’s how I interpreted her somewhat vague comments about STEM, education, and AI.

That might seem innocuous in itself, if it weren’t for the push we’re seeing (at least in the UK, where I live) to gut the humanities across higher education. I’ve witnessed this personally, in universities and departments that I know. While “revitalising” a curriculum in favour of STEM sounds relatively inoffensive, in practice we’ve already seen that it’s not a positive sum proposal—the humanities lose out.

We might think this is an accidental byproduct of the AI push, but I think it goes deeper than that. I think it’s the inevitable result of the kind of thinking that is, in large part, driving AI fanaticism.

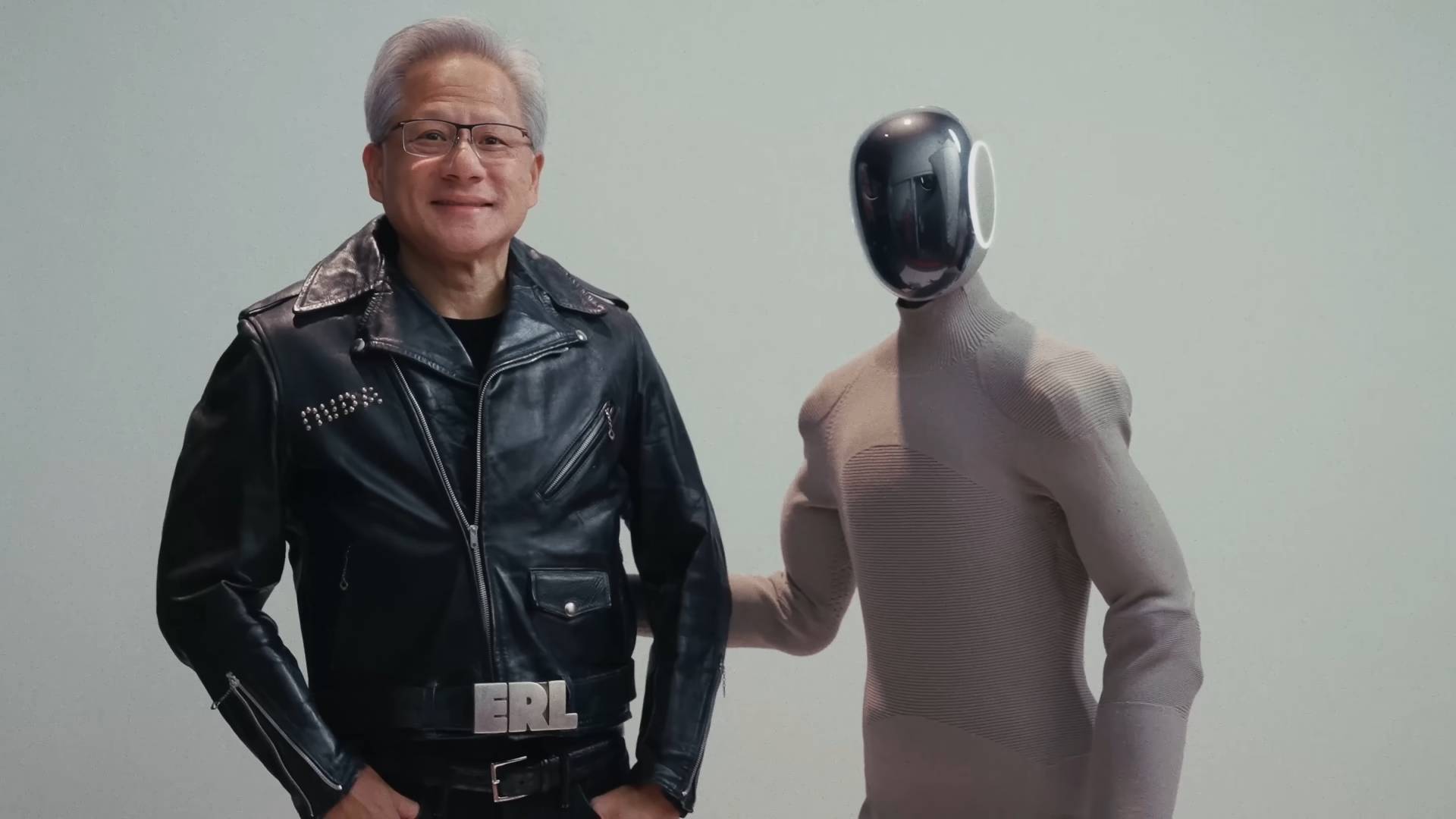

A little after Su, Huang took to the stage in his characteristic leather jacket. Here, amongst other things, I heard him call AI the “great equaliser” because its onset means that “everybody’s an artist, now. Everybody’s an author, now. Everybody’s a programmer, now. That is all true.”

Is it true? Is an AI content writer an author? Is an AI image prompter an artist?

AI aficionados certainly seem to think so. Take Fidji Simo, OpenAI’s new CEO of Applications, for instance:

“When I imagine the future, it often comes to me in images. I paint in my spare time, but the images in my head are so much more realistic and complex than what I am able to paint today. Now, AI is collapsing the distance between imagination and execution. With AI and image generation, I can prompt and iterate until the output matches the complexity and realism of the vision in my head…

“That doesn’t take away from the magic of painting. I still paint—in fact, being able to see my visions on the screen helps me to get them onto canvas. But if AI gives everyone access to the tools to transform their ideas into images, stories, or songs, it will make the world a much richer place.”

Read between the lines here and you’ll realise the argument is just that all that matters on the human side is the imagination. If you can imagine it, you’re an artist—don’t worry about the actual execution, the AI can handle that. The person who can envision The Creation of Adam on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel is just as much of an artist as Michelangelo.

Everybody’s an artist, now

Jensen Huang

Is it any surprise that such disdain for genuine human creativity—which yes, means actually creating rather than merely imagining—would coincide with being uninterested in the humanities? (One way to think of what the humanities is, by the way, is the study of all things human—human life studied in a human way.)

In fact, it’s no surprise that AI fanaticism in general seems to involve such disdain. After all, it’s largely a project to take our own human reason and set it outside our all too human and all too restrictive biological makeups. This, to allow us to push human reason beyond our merely human capabilities.

Not to get too heady or anything, but consider the possibility, just for a moment, that all this could be an attempt at transcendence, a rejection of our limitations, and (arguably on some level) an attempt to become God. (No biggie). If that were the case, it would be no wonder futurists like Ray Kurzweil are so excited, and it would also be no wonder the humanities are threatened given such rejection of our human reality and attempt to transcend it.

And the cause of such a project? An elevation of human reason and a belief that we are progressing towards transcending the human that has its roots in the Enlightenment.

Part of what characterised the Enlightenment was, philosopher John Gray argues (and I agree), the elevation of human reason. Early Enlightenment thinkers such as August Comte and Henri de Saint-Simon explicitly envisioned this as a historically progressive process that would end with a scientific utopia, where scientists, technocrats, and experts are revered like priests, and where humanity, rather than God, is worshipped.

Enlightenment thought in general might not have been so explicit in this, but (Gray argues and I agree, again) post-Enlightenment thought, whether it’s seen in the Jacobins, communists, or neo-liberals, has stuck to the same quasi-religious ‘we are progressing towards a scientific and rational utopia’ idea. The end-goal is often post-human, or rather, human reason but disembodied and transcended.

Under this light, we can see the AI fanaticism of Huang, Su, Kurzweil, Simo, and the whole lot of the new AI vanguard elites, as nothing other than a continuation of the same line of post-humanist scientific-utopian thinking we’ve seen for the past few centuries. The only difference is, this time it looks like there might be a genuine technological means to achieve the anti-human future: AI.

The irony is, of course, that all of this is sold under the pretext of AI’s benefit to humanity (and what technology isn’t sold in such a way?). Yet as I stated at the beginning, the cat is tearing its way out of the bag when this vanguard starts talking about human creativity as no more than imagination and when universities start cleaning shop of the human.

Part of what annoys me about all this is the response to it, though. I think people don’t realise just how deep-rooted of a problem it is. It’s not something that can be solved by yet another discussion about middle-of-the-road AI regulations that seem ever increasingly like attempts to stop a freight train with a piece of rope that might be taut, but is still just a rope.

The problem is deeper, as it’s about how people view themselves and the world, on a pre-reflective level. It’s about how a culture considers itself and technology in what philosopher Charles Taylor calls a “lived understanding”, which is a kind of pre-reflective, non-explicit way of understanding the world.

For the AI fanatics, we are the tools of technological determinism: The post-human is inevitable (“the singularity is near”) and we need to get on board or get left behind. Huang is clear about this: “If you’re not using AI, you’re going to lose your job to somebody who uses AI.”

The future is AI, and we have no choice over it, just get with the program.

Against such Enlightenment faith in the post-human, we require nothing short of a change of lived understanding and a focus on deeper and more difficult questions than how much regulation to impose under the current paradigm. Questions such as, ‘What does it mean to be human?’, ‘When does defending the human per se become more important than improving quality of life with technology?’, and, ‘What is most important for human wellbeing and flourishing?’

(Are you still with me? Hey, AI is heavy stuff, don’t blame me.)

We must challenge this lived understanding, this Enlightenment project that sees the human as no more than a dispensable tool on the road towards scientific progress and transcendence.

Part of this solution might involve re-enchanting the human. Last year I wrote for a sister publication about how PC gaming not always being plug-n-play is a good thing, because it allows us to get involved, somewhat ritualistically, in gaming. I explained how treating gaming as a craft rather than an easy escapist pastime is a good thing.

While [humanists] may have rejected monotheistic beliefs, they have not shaken off a monotheistic way of thinking. The belief that humans are gradually improving is the central article of faith of modern humanism. When wrenched from monotheistic religion, however, it is not so much false as meaningless.

John Gray, Seven Types of Atheism, p24

Philosophers Dreyfus and Kelly explain that this craftsman-like way of being—a poietic way of being, to use the Ancient Greek term—is under threat in our technological age, and I think nothing proves this more than AI and the attitude that underlies fanaticism towards it.

According to Dreyfus and Kelly, we should attempt to re-enchant the world around us, which involves stopping seeing ourselves as active subjects and the makers of all meaning, instead working to open ourselves up to the meaning already out there in things and activities. Presumably, actually creating, not merely imagining and generating, would be one such activity.

That’s part of why I’m a big proponent of gaming intentionally, treating it as a meaningful activity to be appreciated and valued, in part for the creativity that went into whatever game we’re playing. I’ve been bashing the ever-loving faecal matter out of Killing Floor 3 lately, for instance, and while it’s fun to get lost in the dopamine-fuelled progression system, I try to keep myself rooted in understanding that I’m sitting down to connect with other people for a common goal in a game that’s had a lot of time and energy poured into it by real humans, really creating something.

I think the full solution to the anti-human strain of AI fanaticism might involve a little more than this (see here, if you’re interested), but one thing’s for sure: Whatever changes we make, they will have to be fundamental, not ones that stay inside the current paradigm which assumes we are on a path of historical progression, guided by human reason and culminating in scientific or technological utopia. You can’t challenge such thinking within its own framework.

Perhaps a good way to start would be to acknowledge the value of actual human creation for its own sake, not just for what it can give us.

Best gaming rigs 2025

![PlayerUnknown reckons he can take back the term ‘metaverse’ because ‘It’s just been co-opted by certain people… like, I still use Twitter because f**k [Elon Musk]’ PlayerUnknown reckons he can take back the term ‘metaverse’ because ‘It’s just been co-opted by certain people… like, I still use Twitter because f**k [Elon Musk]’](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/MAnk2phqV9dfo44qo26yMN.jpg)