I spent 14 hours flying 6,230 miles to watch MSI make me a new motherboard in just 40 minutes

Sometimes it’s quicker, sometimes longer, but I watched a bare printed circuit get turned into a fully fitted and boxed motherboard in just 40 minutes. It was followed by another just a few minutes later. And then another and another. The line never stopped and wouldn’t do for up to 20 hours every day. In total, all of the manufacturing lines together could potentially turn out 1.3 million motherboards every month.

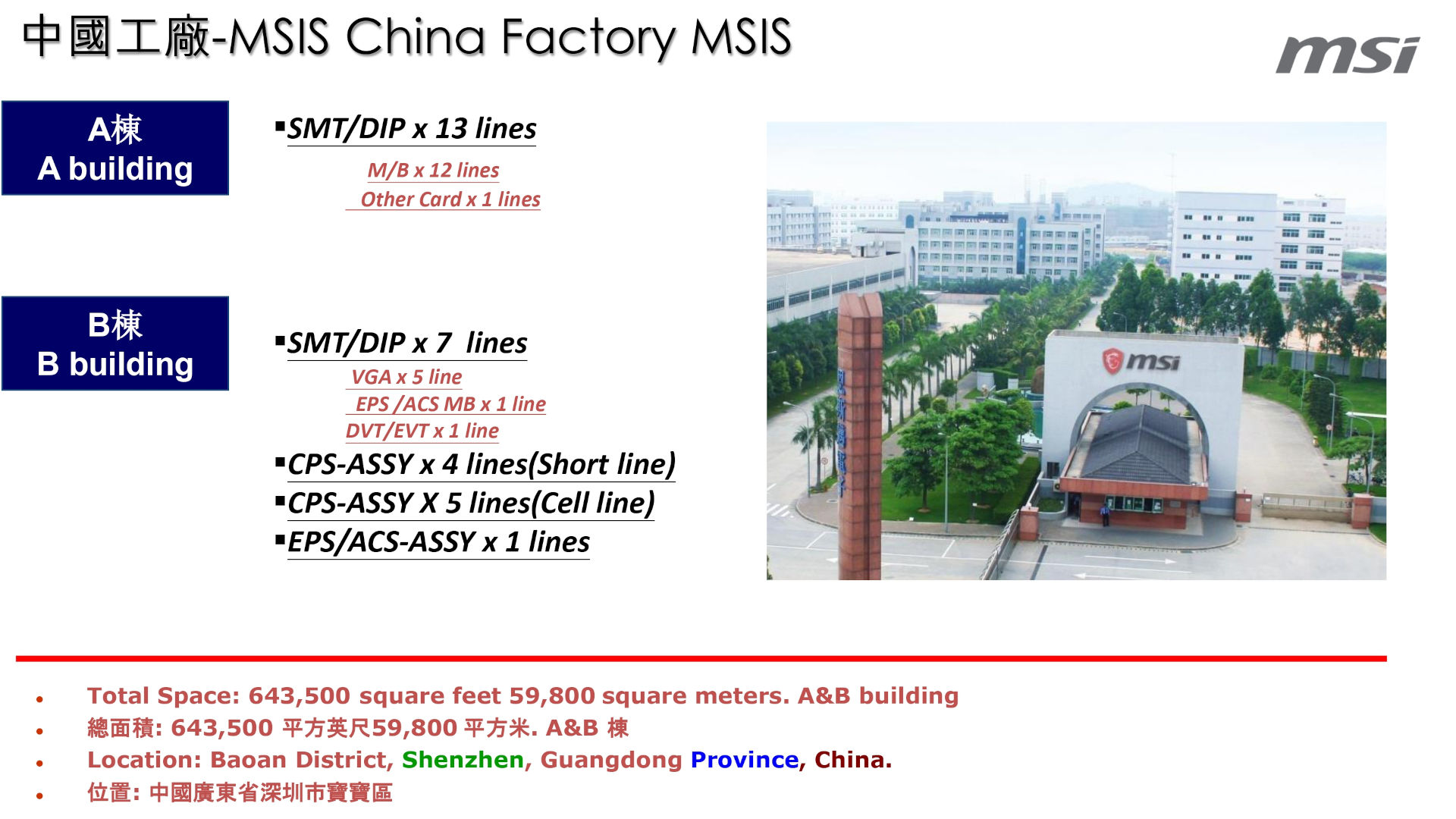

That’s according to Micro-Star International (aka MSI) who invited me and a raft of other tech journalists to visit its primary manufacturing site in Shenzhen, China. We were given an in-depth tour of the motherboard production lines, along with some smaller lines making AIO and mini PCs, plus some early glimpses of new models coming soon.

The site where everything happens is huge: 200,000 m² in size and hosts four production facilities, including warehouses, test labs, and offices, along with six buildings for living quarters and the like. Yes, that’s right, a large portion of MSI’s workforce lives on-site but that’s not unusual for the industry in China.

It’s not just motherboards that are made at MSI Shenzhen, as graphics cards, desktop PCs, servers, and even components for the automotive world are manufactured there. It was first built around 23 years ago and has been steadily modernised to meet the demands of the world of computing.

My first impression of the factory was one of relief—it was uncomfortably hot and humid outside but blessedly cool indoors, even in areas that didn’t have active air conditioning. The same was true of the main motherboard production area, though, for our visit, most of the lines weren’t operating.

After a morning showcasing new products, MSI walked us through its manufacturing process for motherboards. Much of it is heavily automated, with humans only involved in specific aspects—quality control, testing, repairs, large component mounting, and final boxing. All of the tiny resistors, capacitors, and inductors are fitted by machines.

Once everything was explained, we split up into small groups and then walked into the primary motherboard production facility. My second impression was one of familiarity, as I used to lecture about manufacturing engineering for many years, and I recognised an awful lot of the machines and procedures.

Some of the equipment being used was older-looking than I expected, particularly the robotic arms, but for the most part, it’s as modern as one would imagine it to be. If one has an image of manufacturing in China being dirty and unsafe, then it’s an entirely wrong picture of how everything is at MSI Shenzhen.

At one point, one of the operators managing the surface component mounting machines was chided by a senior member of staff for allowing a waste roll of parts to fall onto the floor. I should imagine some of that was due to the presence of media but I spent a bit of time just watching various operations take place and it became clear MSI runs a very tight ship.

The slides and images in this article highlight the various stages of making a motherboard but as a general overview, it goes like this:

- A blank PCB is inserted into the production line and then solder paste is applied to the bottom of the board.

- The board then moves into a machine that applies surface components, before it moves off into a long oven. This is used to melt the paste and bond the components to the board.

- It takes a while to run through the heating process but once done, the PCB is passed through an automated optical scanner which checks that all of the parts are correctly mounted. These stages are then repeated for the top-side components.

Certain parts are added by hand because MSI says there aren’t robots good, or fast, enough to do the job.

Certain parts, such as VRM heatsinks and DRAM sockets are added by hand because MSI says there aren’t robots good, or fast, enough to do the job. I’m not sure that I necessarily agree with such a statement but some components are probably just too fiddly to be inserted by a machine.

Once the main part of the building phase is done, the quality control testing stage begins and each board is taken off the line for electrical testing. Once passed, it’s added back to the line for packaging and final boxing. There are multiple stages where checks are performed, either by machine or by eye, and there’s even a dedicated repair stage to fix any little niggles.

It’s a relatively quick process, although it does depend on the motherboard model. Top-end versions, replete with all kinds of heatsinks and other surfaces, take longer to build than the basic ones. However, it’s pretty much the same number of people involved, probably no more than 15 in total.

MSI is proud of the fact that so much of the production line is automated and as consumers, we certainly benefit from this, as it means there’s far less variability in the quality of the motherboards and it helps to keep the cost of them down, too (though they are mightily expensive, these days).

The downside to this is that while MSI Shenzhen was originally designed to employ and be operated by nearly 12,000 people, the factory now only employs around 3,000. It’s obviously not the only large-scale manufacturing industry that’s gone this way but for a country as populated as China is, it must surely add a lot of pressure on workers and potential employees to retain their jobs or get into MSI in the first place.

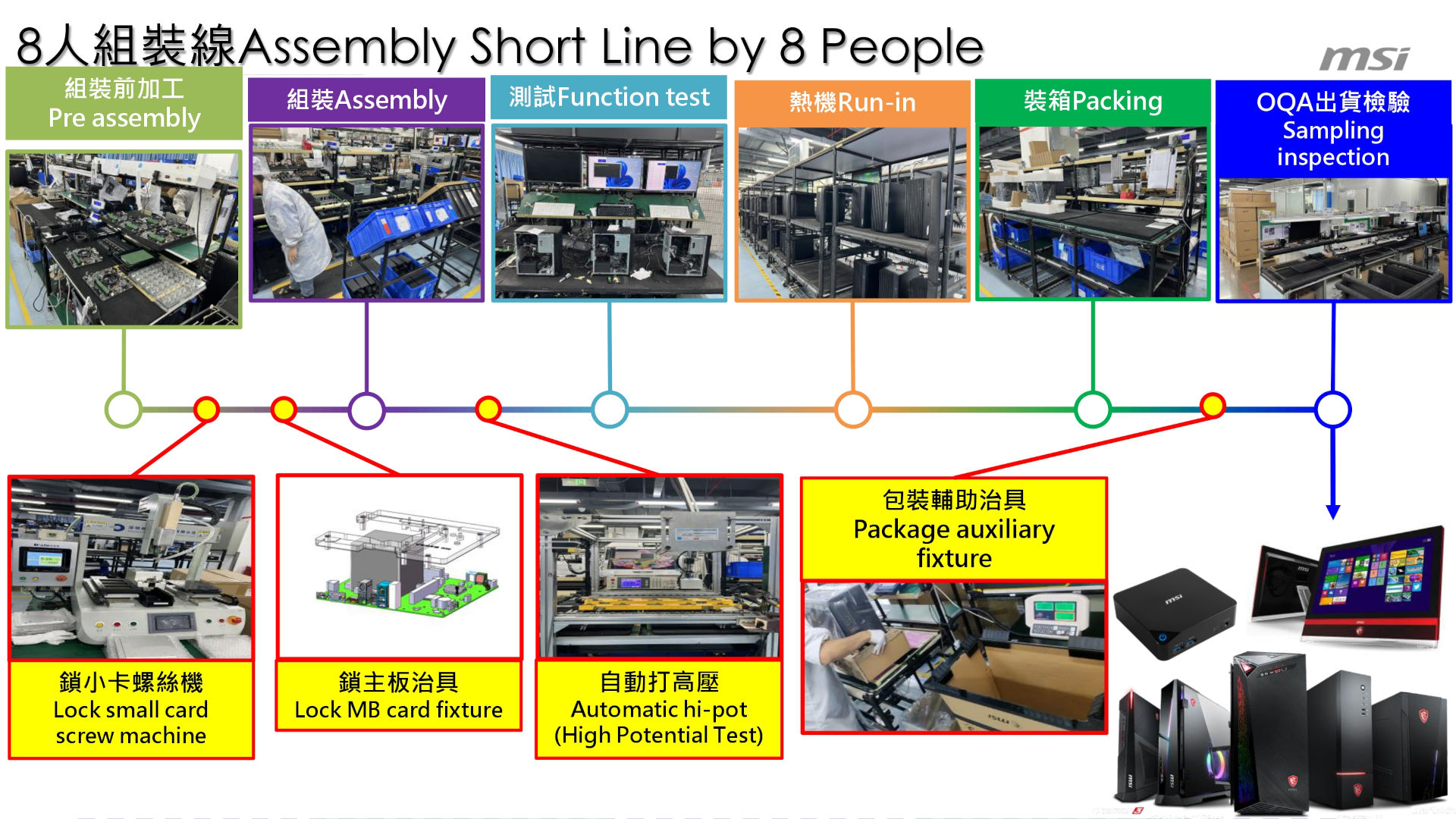

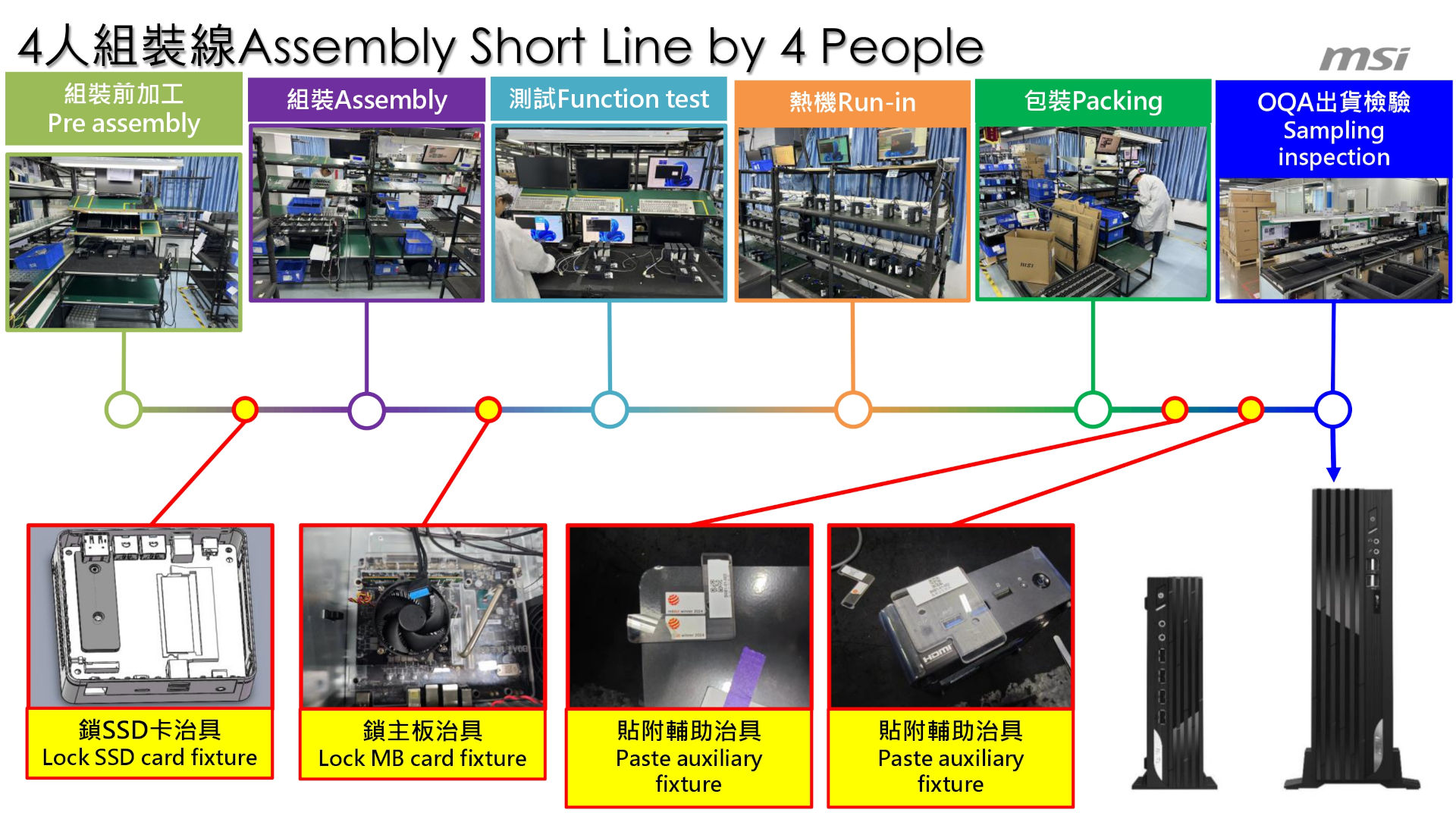

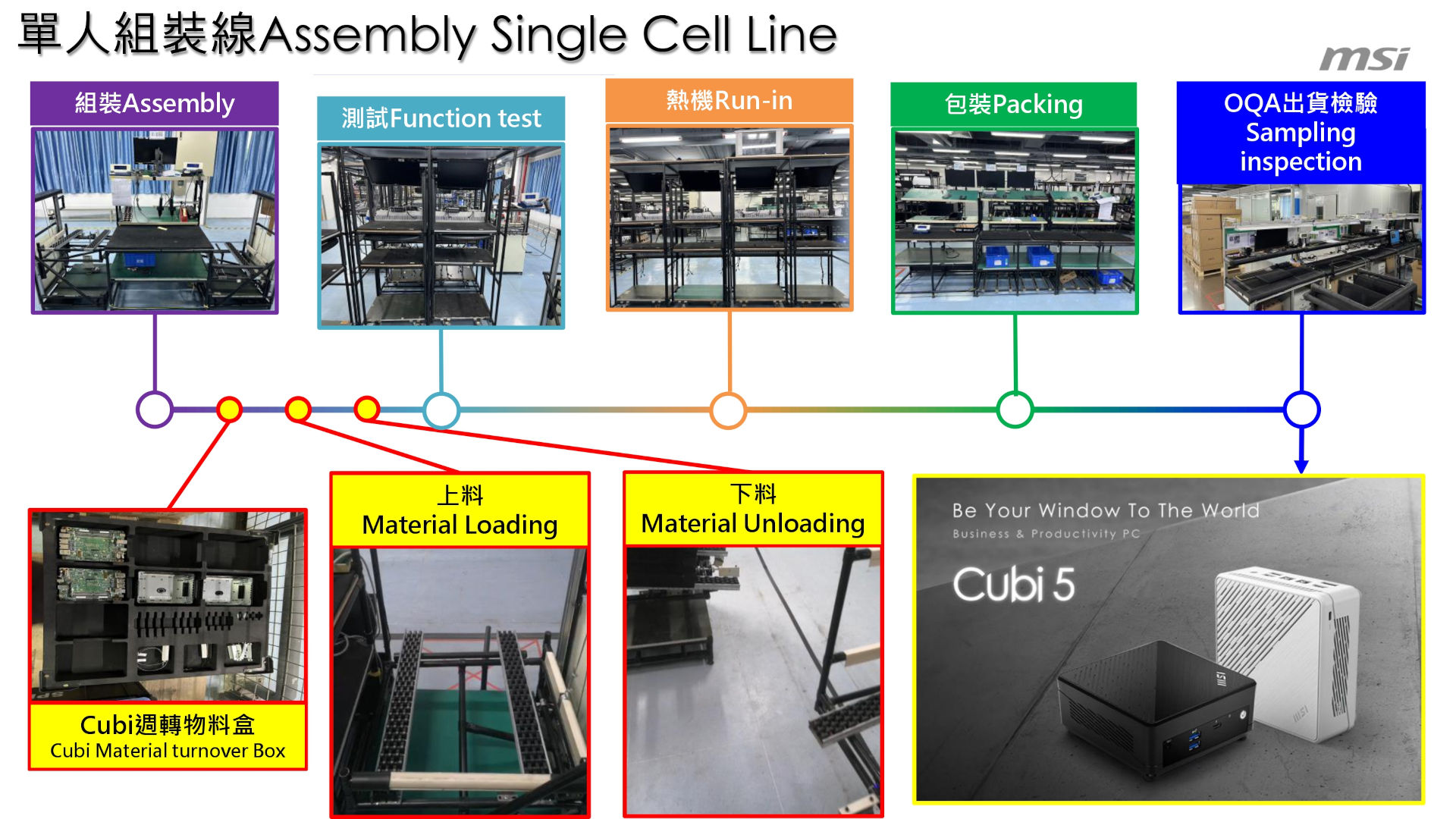

Fortunately, from this perspective, there are still many areas where it’s humans all the way. The smaller production lines, such as those for mini and all-in-one PCs, were entirely hand-processed, bar machines to just move items along (plus some cute little robots travelling around the shop floor).

The quality control and electric testing of all those PCs is also done by hand and it’s somewhat reassuring to know that a genuine person is checking the PC you may end up buying runs properly. Whether that’ll be the case in another 20 years is anyone’s guess, though.

Although we only got to see a very small section of MSI Shenzhen, the sheer scale of the operation was evident. The inventory and surface component recycling sections were large, busy, and heavily computerised. Wagons were constantly dropping off materials and taking finished products away. Workers en masse stuck rigidly to routines, clocking on and off, taking lunch breaks, and so on.

I as write this, I have two new MSI motherboards on my desk, ready for testing and review. It’s funny to think that I could have seen one of them being made in front of my eyes just a few weeks ago. I certainly have a newfound appreciation for the journey it, and millions like it, have gone through to get here.

Now, how can I get back over there and sneak into the graphics card production line to see some nifty new GPUs being put together?