China: Mao’s Legacy is like an absurdly specific Paradox game on a tight budget, and also one of the best sims I’ve ever played

“China,” observed Charles de Gaulle*, “is a big country, inhabited by many Chinese people.” You can’t knock the guy: he was right. There are loads of Chinese people in China, it turns out, and they’re all upset with me specifically. My strategy of allying with the most widely despised people in the nation has not paid dividends. The wars I have gotten us into? Unpopular. Loosing the army on a funeral? An ambitious, some might say courageous move, and yet not one that has earned me friends.

But that’s the way it goes in China: Mao’s Legacy, a rickety political strategy game from the same studio that put out such bangers as Crisis in the Kremlin, Ostalgie: The Berlin Wall, and Collapse: A Political Simulator. Canny readers will note a theme here—simulations of historical epochs that you might politely call ‘transitions’ or honestly call ‘disintegrations’.

Mao’s Legacy is no different. The game kicks off in April 1976. Former premier, consummate diplomat, and archetypal reformer Zhou Enlai has been dead for three months. Mao Zedong—the chairman himself—is visibly ailing. Factions are already vying for control over the post-Mao direction of the country like dogs over a T-bone steak.

I am not equipped to deal with any of this. I am Hua Guofeng, China’s doomed and hapless premier who briefly assumed leadership over the country in the aftermath of Mao’s death. You probably don’t know his name for two reasons. One, he was swiftly ousted by Deng Xiaoping and the Chinese reformers who would set the country on the course it remains on today. Two, his most notable contribution to China’s political thought is a policy literally called the “Two Whatevers.” His was not the substance of which the great people of history are made.

Sailing the seas depends on the helmsman

Unlucky for me, then, that I can’t be anybody else. Your goal in China: Mao’s Legacy is, more than anything, to keep a grip on power. Everything else is subordinate to that. This is why the first two entries on the game’s charmingly homespun (almost Flash game-like) UI record your popularity among the party and your popularity among the people simultaneously.

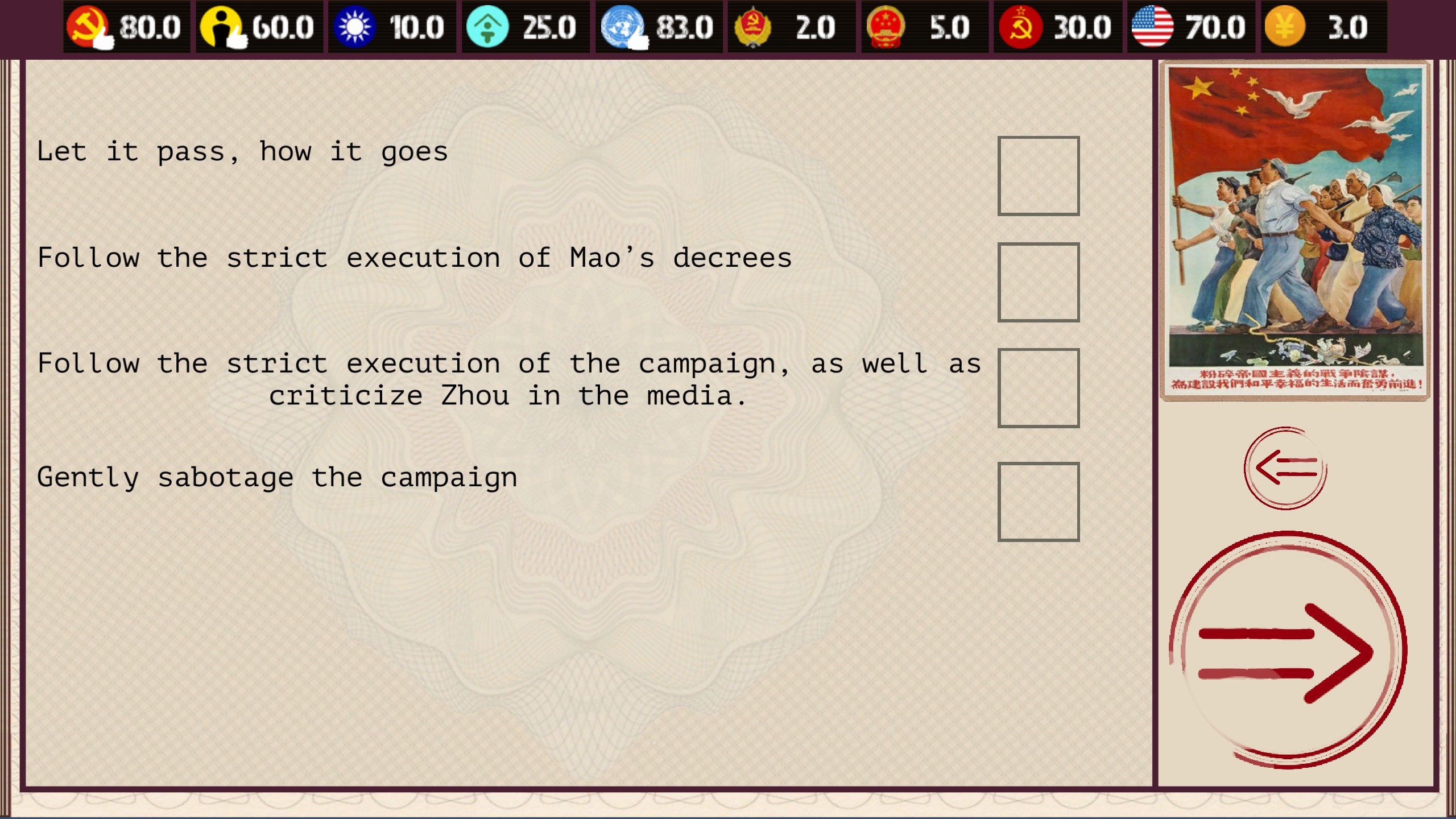

What happens to them is mostly event-driven. As the days pass by, you’ll be hit by circumstance after circumstance after circumstance, all modelled after real historical events: How do you respond to the 1976 Tiananmen Incident? How do you deal with the Gang of Four? Should you cremate Mao according to his wishes or set him up in a Lenin’s Tomb-like mausoleum on Tiananmen Square (no points for guessing which one happened in real life)?

How you respond to these events can have major and immediate consequences for your political standing. By throwing in with the ultra-leftist Gang of Four, I won the ardent support of some party factions, but earned the bottomless hatred of every moderate and reformer in the Central Committee. The same applies to international affairs: did Uncle Sam like it when I sent guns to Maoists over the globe? He wasn’t thrilled about it.

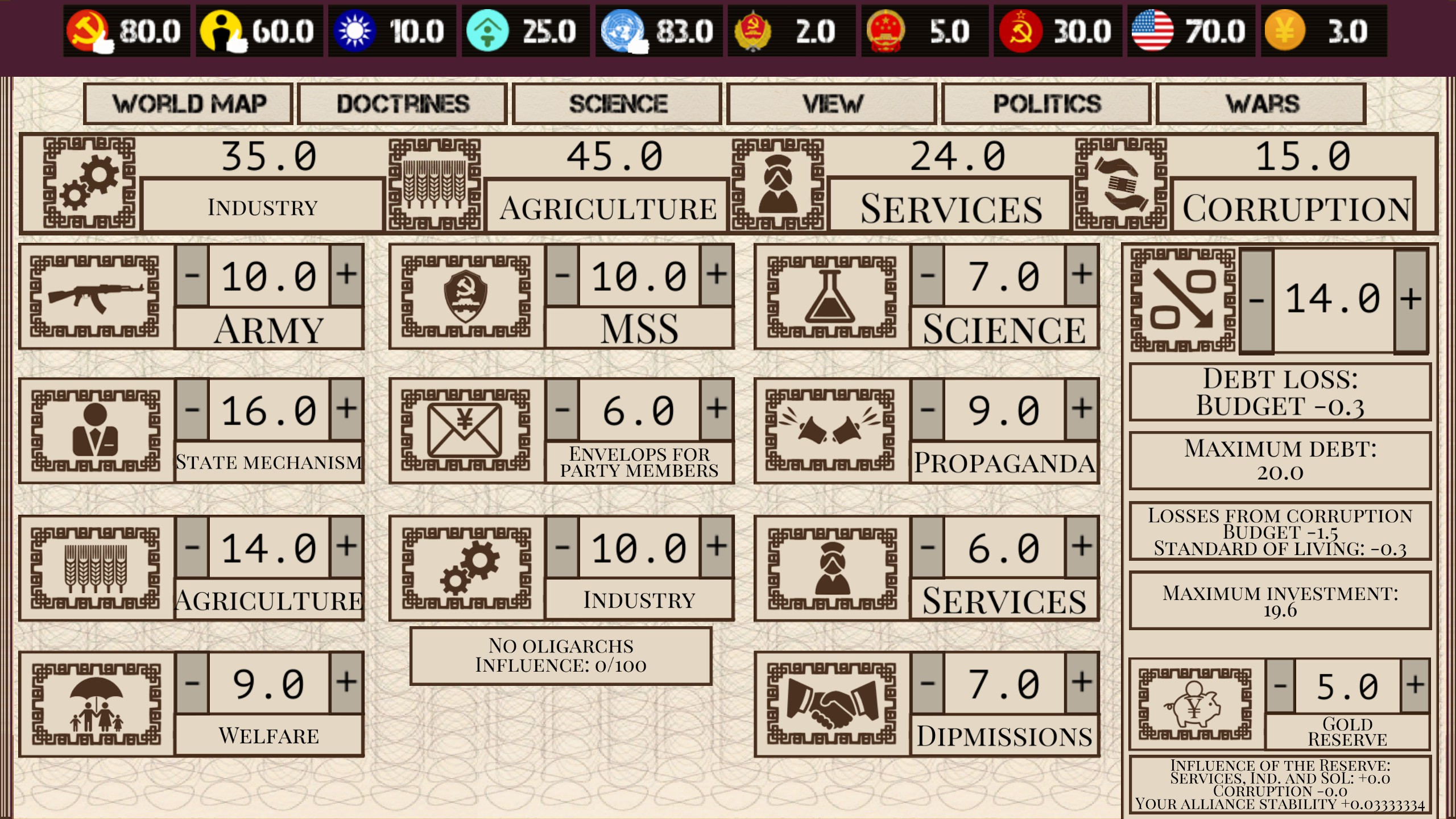

But you also have buttons to push and knobs to twiddle to adjust your longer-term prospects. If I were to compare Mao’s Legacy to anything, it would be a kind of ultra-budget Paradox game: CK3 on the back of a few bucks. You can flick between screens to muck with the budget, tinker with your international diplomatic stances, set domestic policy and all that other stuff you’re used to doing in the Europa Universalises of the world. Dump your budget into propaganda and welfare and your popular support will go up, drop it into the bureaucracy and the party will like you more, use it to grease your comrades’ palms and, sure, their opinion of you will skyrocket, but you’ll also send corruption through the roof.

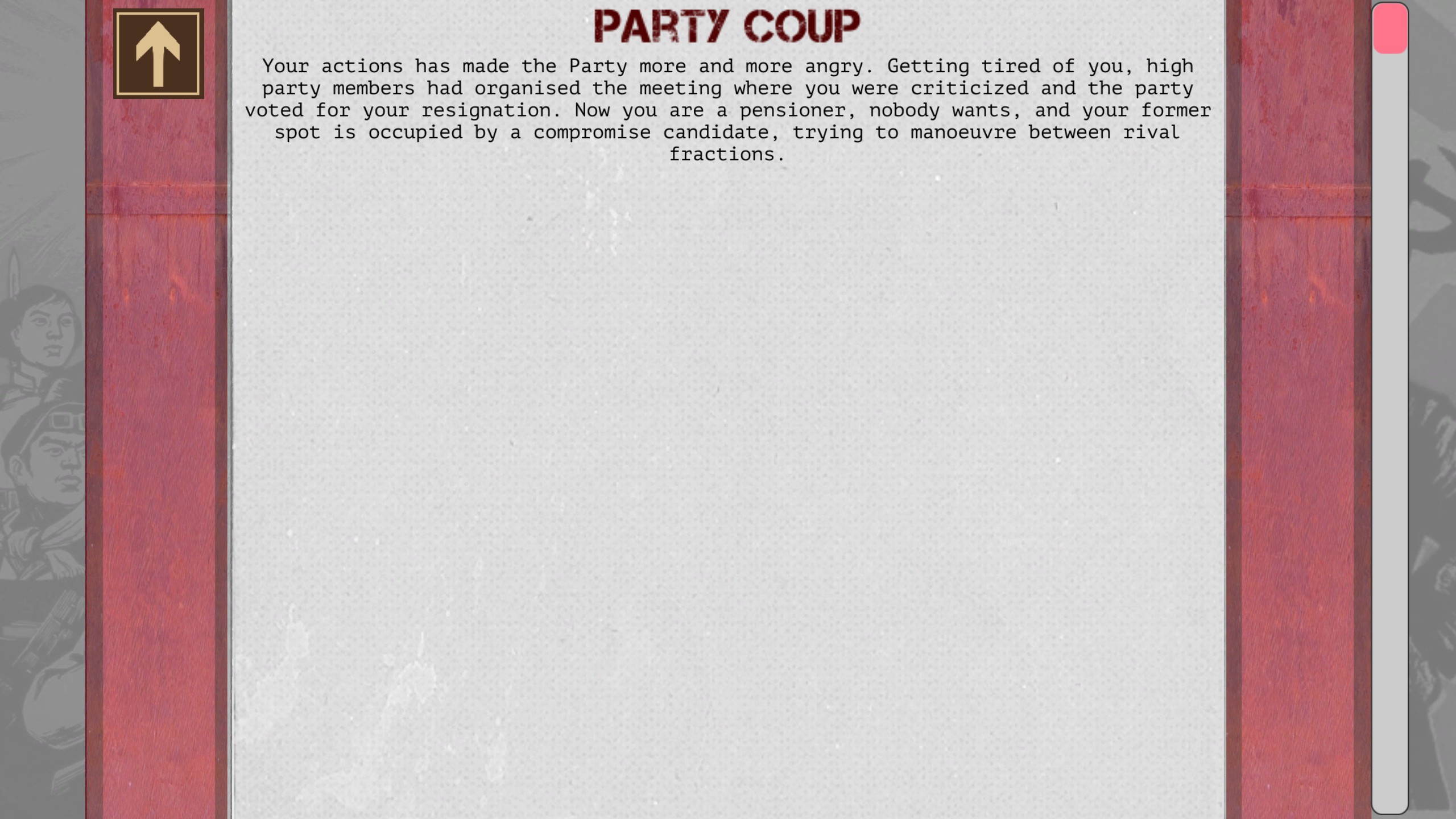

When my first attempt at the most ultra-leftist administration possible ended with the people politely yet firmly explaining I was not in charge anymore, I dumped all my money in the next game into keeping them happy: a welfare state, constant propaganda, increased standards of living. I still took dings for every event that I took the most communist option possible in, but the drip-drip-drip of positive opinion that came in as the months went by kept my head mostly above water. That is until the party decided it was sick of me subjecting everyone to show trials and struggle sessions and forced me into early retirement. What’s the problem with the odd show trial? They keep you on your toes.

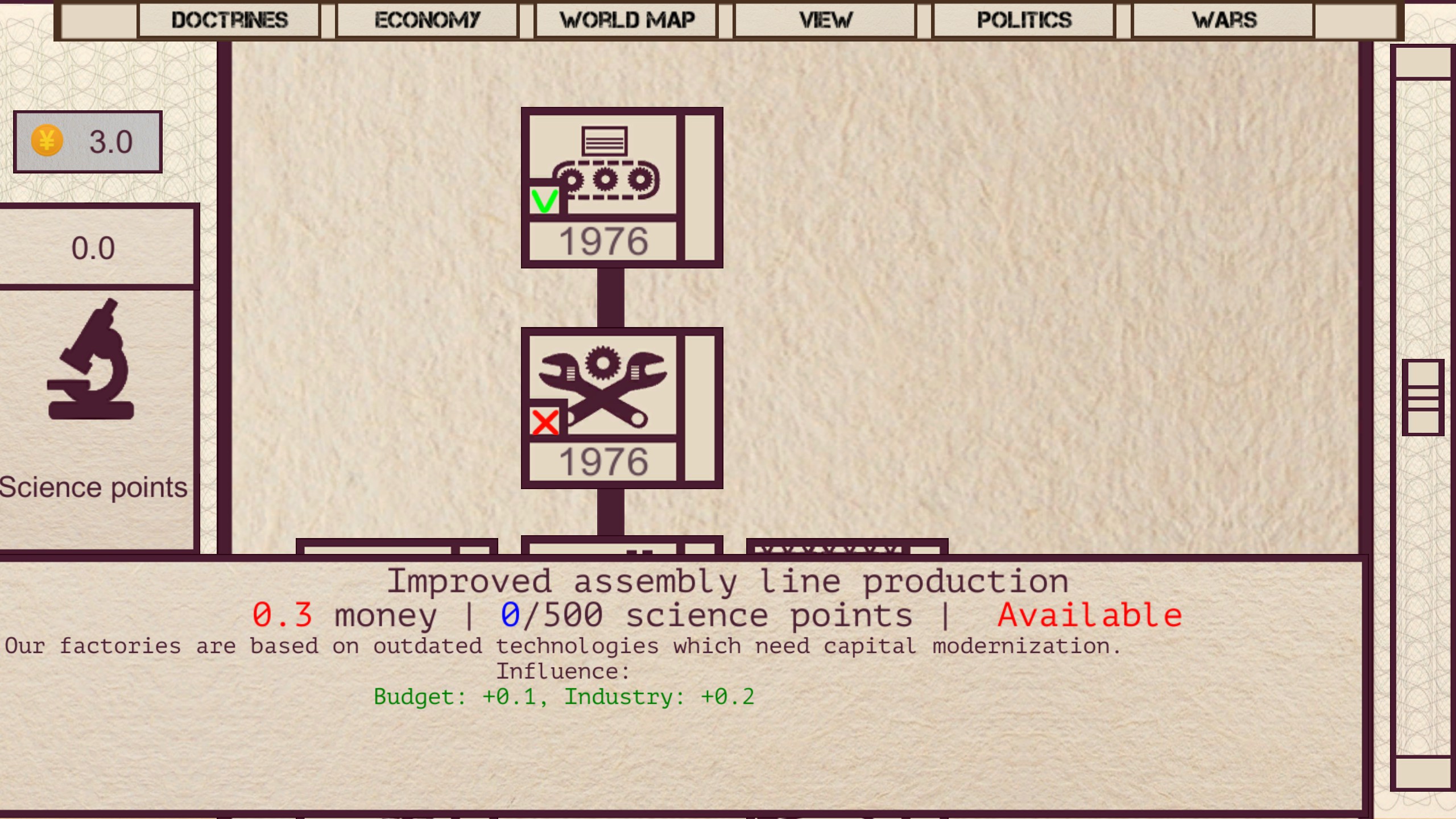

Next round? Trying to fix that too, dividing my annual budget between the party machinery and buffering my public support. I even directed our scientific research (there’s a tech tree) into better industrial technology to try to give me more money to spend on all these ingrates. It worked for a little bit, but not forever.

It soon becomes clear that following the historical route—reform and opening up—is the path of least resistance. I don’t think that’s a flaw. In fact, it might be what I find most admirable about this strange, scrappy little sim that looks partially like it was made in MS Paint. China in 1976 was tired, and looking for a new direction. Radicalism had produced the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution, two events that public and (the majority of) party opinion regarded as catastrophes. I couldn’t just flip a switch and get everyone hype for the revolution again.

At the same time, of course, both party and public were committed enough to the revolution for which so many had fought and died that you couldn’t just flip a switch and transition the whole country to some kind of humdrum capitalist republic, either. Under those conditions, of course Dengist state-led developmentalism is the easiest path to pursue. Living standards go up, the revolution endures, and no one gets plunged back into the pseudo civil war of the Cultural Revolution. It’s a real triumph of this weird, rinky-dink little game full of strange UI and slightly garbled English that it manages to capture that so well.

But also, I don’t care. Next time through we’re building supersonic-communism, baby. I just have to find precisely the right way to allocate this month’s budget.

*This quote is likely apocryphal. However it is also very funny, so let’s all agree that he said it anyway.