Luto is an underappreciated 2025 gem about the horrors of being held hostage by your house

It’s happening again. You’ve ignored your body’s alarms and pushed yourself well beyond the threshold of exhaustion. It’s Monday, or maybe Thursday, but who’s keeping track anymore? Your body moves independently from thought—either unconcerned or incapable of addressing the growing detachment—and you repeat the same, torturous daily routine with a mechanical ease.

You’re not physically held hostage, but the belief that you’re trapped becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. That’s the crux of Luto, a first-person psychological horror game aesthetically similar to P.T. and narrated by The Stanley Parable’s distant cousin. It’s confusing, terrifying, cheeky, and touching all at once. I beat it in just two short sessions over the holidays, but that was enough to turn me into a snotty, blubbering mess by the end of it all.

“It’s a game about grief,” I say, like it’s some profound declaration you’ve never heard. That may be a particularly draining statement about a game released in the same year as another anguished darling, Clair Obscur: Expedition 33, but we’ve been trying to figure out how to best express loss since humans first carved their portraits of grief into cave walls. And while it’s only five or six hours of first-person horror, Luto is quite good at simulating what happens in the face of unbearable absence.

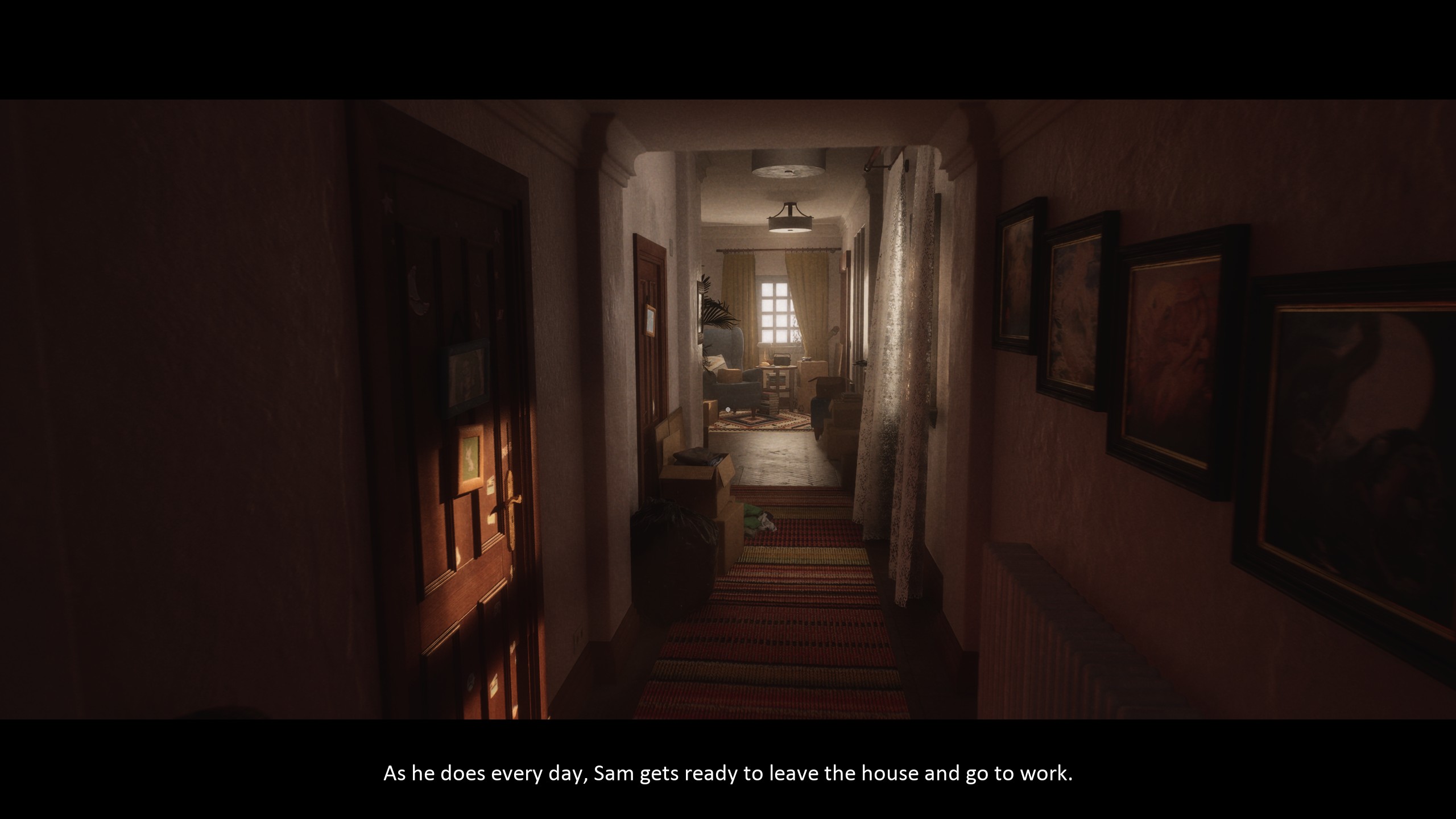

When I think of P.T. inspired horror games, Visage is the first that comes to mind, though Luto isn’t nearly as big on the in-your-face terror. They share the same tense dread (along with the occasional jumpscare), sure, but their biggest commonality is the environmental tricks deployed by a house holding you hostage. It’s all normal at a glance, but there are secrets in the walls.

As Sam, you’ll repeatedly try (and fail) to reach the front door while the house and its omnipresent narrator grow more antagonistic with every attempted escape. No matter how hard you try, there’s always something barring Sam from the exit. You’ll find his keys, turn the knob to leave, and suddenly the screen goes black. The day is gone. You tried to exit on a Monday, but now it’s Thursday, and you’re in the bathroom with no way to account for the lost time. We’ve all been there.

He’s like a tormented version of Bill Murray in Groundhog Day, but swap out all the fun romantic comedy bits with ghostly mannequins, dark hallways, and strange noises coming from the basement. Sam’s inexplicable, disorienting reset often happens with little or no warning, and that’s what I like so much about his impossible journey to go outside. There’s an oppressive sense of something being very off from the beginning, like it’s clear someone or something doesn’t want you peeling back the layers. A vague, threatening aura of don’t open that door, you won’t like what’s behind it.

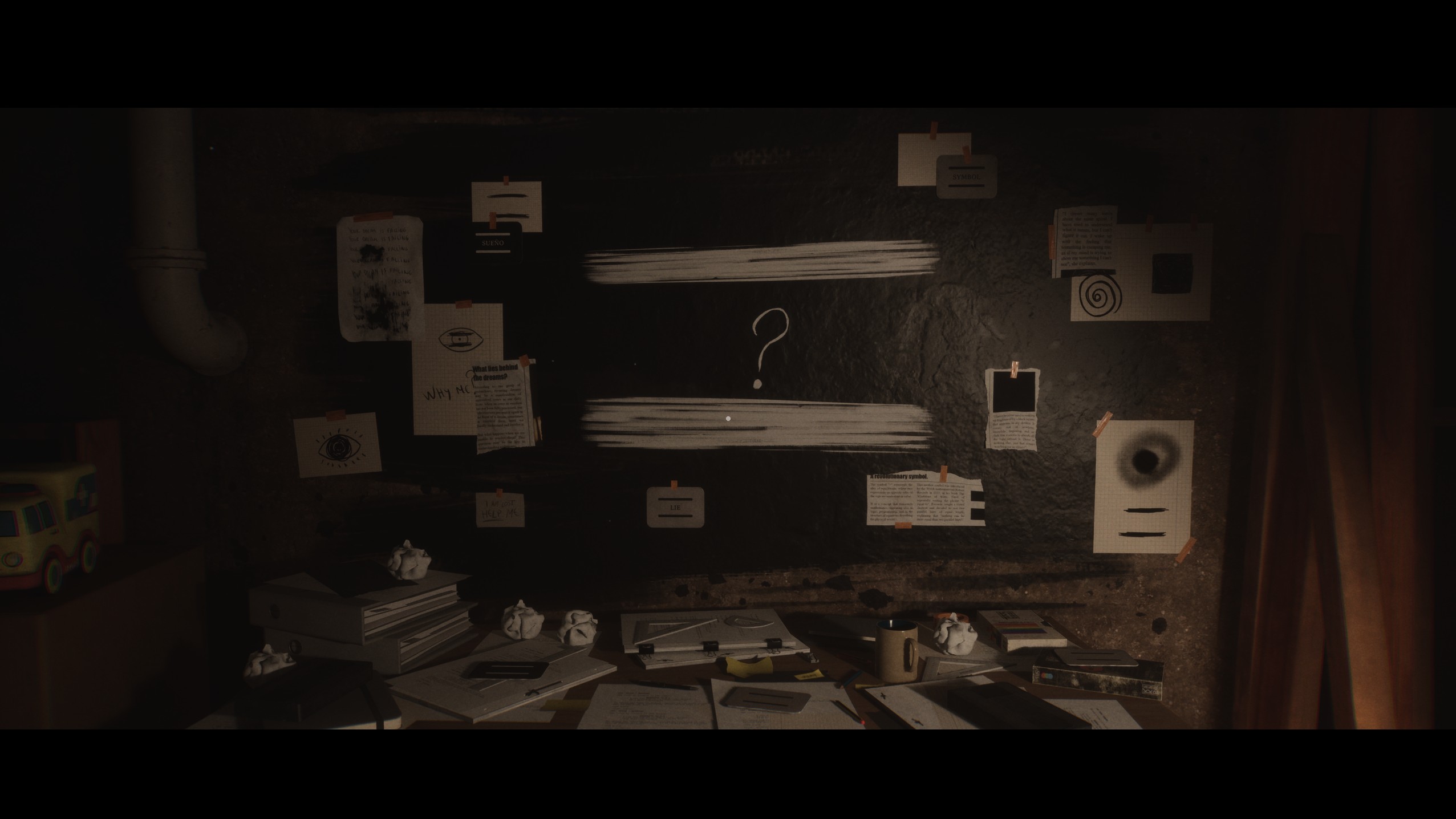

The pictures and mementos scattered about are all you need to understand Sam was going through something long before your place in the story, but the excessive languishing muddies the picture the longer it goes on. Every time I thought I had a solid theory for what was keeping Sam a prisoner, Luto added another puzzle or unnerving anomaly into the fold. Its mysteries aren’t cliche or straightforward enough to solve that fast, and even when you make meaningful progress, the house and narrator will retaliate.

When Monday suddenly becomes Wednesday, Luto’s disembodied voice carries on narrating the day like discovering secret rooms and walls with graphic depictions of death are normal parts of Sam’s routine. As the days shift and add on more puzzles, their solutions and clues begin to overlap, and after a while, I can’t remember what the hell I’m doing. It’s an uncomfortable feeling Luto masterfully taps into, recreating my own occasional depressive meandering when I move from room to room and can’t remember why I even entered in the first place.

Luto laid its haunted protagonist bare in an existential trial that left me questioning myself just as much as I questioned Sam.

Sam tries to account for the entropy, but the tension between him, the narrator, and my own beliefs reached a point where I couldn’t identify who was the least reliable unreliable narrator in the setup. Was it me, Sam, or the cheeky voice of god? I don’t know, honestly, but the psychological horror of it all certainly did its job. Most of my fear stemmed from the excessive hypervigilance Luto builds through doubt and an eerie sense of, ‘that’s not how this room looked before.’ Jump scares be damned.

At the end of it all, when I was done collecting clues from the past and trying to make sense of this impenetrable mind palace, Luto laid its haunted protagonist bare in an existential trial that left me questioning myself just as much as I questioned Sam. While I had my guesses, Luto’s disorienting maze is good at instilling uncertainty until its final moments, and even then, Sam’s house of grief remains uncomfortable and complicated.

It’s a discomfort I wholeheartedly welcome, and a door I’m glad I opened.

If you want to join me and ring in the new year with a poignant, bite-sized horror adventure you can finish in a session or two, then you can check out Luto now on Steam.