Interview – Slave Zero X’s Art Director Francine Bridge And Character Animator Scott Brown Discuss Slave Zero X’s Influences And The State Of ‘Retro-Inspired’ Games

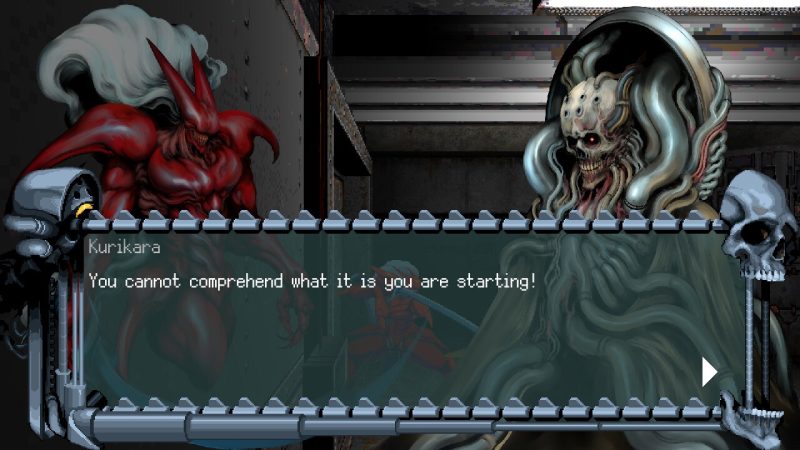

If Slave Zero X wasn’t already on your radar for games to play in 2024, then add it to your list. This retro-inspired side-scrolling action game mixes the complexity of a 2D fighting game with high-octane action into a futuristic dystopian adventure, where its the player character against an evil regime.

It’s also a prequel to the classic Slave Zero that released back in 1999, with both games taking place in the concrete jungle that is Megacity. Developed by Poppy Works, this new action game is an example of how, as art director Francine Bridge puts it, “It’s not a throwback anymore,” when it comes to what I called a ‘growing desire’ for retro-style, retro-inspired games.

For Bridge and for character animator Scott Brown, they don’t see the styles they’re working in as retro, rather they’re just continuing to innovate and create in ways that, in reality, are no where close to being creatively exhausted.

I got to spend the better part of an hour speaking to Bridge and Brown all about what that looks like for Slave Zero X, what helped inspire and influence them, and what makes an action game feel really fun to play.

Interview – Slave Zero X’s Art Director Francine Bridge And Character Animator Scott Brown Discuss Slave Zero X’s Influences And The State Of ‘Retro-Inspired’ Games

What’s Old Is New Again, And How We Got Here

Firstly, I wanted to know how Bridge and Brown both got involved with this project. For Scott Brown, it was a simple DM on Twitter from Wolfgang Wozniak, chief executive officer at Poppy Works. Wozniak asked if Brown was looking for work, they spoke about Slave Zero X, and Brown couldn’t say yes fast enough.

“He showed me just a few pieces of Francine’s work and like the earliest start of the in-game demo stuff and I was immediately like ‘Yeah, I want to work on this, this is something cool…as soon as you can get me onto this, I’d love to be a part of it.”

For Francine Bridge, she was part of the original team that pitched Slave Zero X to its publisher Ziggurat Interactive. “I basically dedicated my career to painting monsters for money,” she says, and with that backlog of her highly-crafted monster paintings, cold emailed the person who would become the game’s director, Tristan Chapman.

“I came on to Slave Zero X because a couple of years ago I cold e-mailed Tristan Chapman. a.k.a ‘Sinoc’ who would later lead part of the development on Slave Zero X about his game, Devil Engine, which at the time was about to bring out Devil Engine: Ignition and I said ‘I love the way your game looks, I don’t normally cold solicit people but if you ever need someone to do any additional promo art or something like that, I’d love to.’

They got back to me a couple of months later and actually responded positively, and I was able to work on a large piece of promo art for Devil Engine: Ignition which was used at Tokyo Game Show and is now I believe the Japanese game cover for the recent release of Devil Engine.

I didn’t talk to Tristan for a couple more years, then in late 2020, I was up very early in the morning and I received a message from him saying ‘Do you want to come and pitch on a game with me and Wolfgang [Wozniak]?’ and the rest is history.

I went with Tristan into a Discord that we set up, and we got a pitch together for the game that would become Slave Zero X. After that I was able to get the position of lead artist and art director on the team, which was my first senior role and my first time directing other artists like that.”

That’s how Francine and Scott came to work on Slave Zero X, but in terms of how Slave Zero X got here and the action game it is today, that’s a longer story with an artistic through-line drawn by Bridge, briefly as she can.

“Talking about the inspirations for Slave Zero X is really broad field, basically because there were so many different things coming into it. Not just the inspirations we inherited from the original but the inspirations that we wanted to bring into Slave Zero X to make it distinctly ours and to expand on that so that we weren’t just retreading the same ground.

The way I’ve summarized it before in interviews is that the original was kind of created off this inspirational reflection of the first big wave of Japanese pop culture moving over into the US. The first mainstream exposure that a lot of people had to stuff like Neon Genesis Evangelion or Bubble Gum Crisis or Ghost In The Shell or any of those Yoshiaki Kawajiri OVA’s like Ninja Scroll and stuff like that.

There was this big response where suddenly everyone wanted to do something like that was inspired by this, and Slave Zero was kind of born out of that first big explosion of cultural exchange. I think for us, Slave Zero X was about returning to that but with 20 years of additional time having passed, and now the way that pop culture interacts with manga or anime or any of those creators I’ve named has changed, and there’s a much wider understanding and a greater number of more niche creators.

So stuff that we wanted to bring in, like, I love Tokusatsu cinema and tv, where you have transforming heroes like Kamen Rider or the Sentai shows. Keita Amemiya was a director who was hugely important to us, he did a film called Mechanical Violator Hakaider, which is about a resurrected android in a post-apocalyptic scenario who marches through a million trooper guys and punches their heads off in order to kill a silver-armored separate rival android and then eventually the leader of this sort of weird, cult government that’s been created.

So you can see it maps almost one-to-one to Slave Zero X in a lot of ways. Mechanical Violator Hakaider was a huge influence for us, and the reason I wanted to slide into that one is because it kind of ties into something that we talked about early on related to that responsiveness in gameplay.

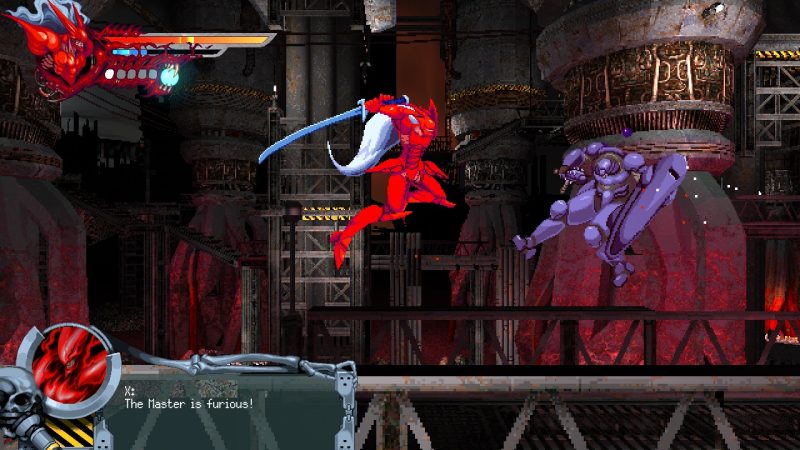

There’s a scene in Hakaider where, Hakaider and Michael, the two rival androids of the film are in a fist fight, and the sound design and the way that the scene is shot is designed to convey the idea of entities that are made of incredibly dense metal colliding with each other.

It’s just a regular fist fight, it’s very slow-paced by comparison to something like, say a Sammo Hung fist fight in a Hong Kong martial arts flick. It’s very slow, it’s just two guys slugging each other. But the way that it’s conveyed, there’s this deep ringing metallic noise that happens every time they connect with each other and you see stuff crack around them and pillars get broken and the whole surface of everything shakes.

That responsiveness, the fact that they took very simple emotions and made them feel like 200 tons of stuff colliding into each other was a big part of what we wanted for Slave Zero X. When Shou does the charge punch where he pulls his fist back and you see this coursing light that Barbera [Boone] on the animation team, Barb animated that.

When you see it gather in and he pushes it forwards, it has the capacity to go through several troopers at a time and they all explode and 400 rib cages come out of them because it’s kind of like the Mortal Kombat ridiculous guts thing where everyone has four people’s worth of guts inside them and they all go flying back against the wall.

Conveying that what you’re seeing represents something that is much denser or more powerful, even that kind of call and response of motion to massive reaction is part of what makes a lot of anime and Tokusatsu and everything, that’s part of what of really spoke to people when it first came across.

So the two are intrinsically linked, the original inspirations that inspired Slave Zero and that now we’re echoing back again with Slave Zero X and stuff like action game responsiveness. I think everyone’s been influenced by work coming out of the Japanese animation industry over the last two decades and that’s really core to it.

The two questions kind of overlap, what inspired Slave Zero X and what makes a good action game, it’s kind of one in the same in a lot of ways. That’s a very brief summary of the inspirations, there’s a lot of other stuff.”

Bridge also talked about how when speaking to the art director on the original Slave Zero, Ken Capelli, they both discovered that garage kits sculptor artist, Yasushi Nirasawa, was an inspiration for both of them.

“It was interesting to find that even the inspirations I thought were something that was more recent, was already present in the original, so there’s a very strong through-line.”

As a side note, if you couldn’t tell Francine has a deep understanding of the art she works in, and great taste, further exemplified by a moment in our conversation where she was showcasing her Nightingale and other Gundam figures.

“Making A Game For The Dreamcast 2”

You don’t need me to tell you that making a game is a very, very difficult and arduous process. We hear it from game developers all the time that being a game developer is hard work, but that doesn’t stop the players who’ve not tried making games from having huge misconceptions about game development.

One of the biggest being that if you’re making a game that’s using pixel-art or anything that appears to be retro, it’s easier to make those games compared to your big AAA(A?) realistic-looking, graphically supped-up games.

It should be obvious that statements like that aren’t true, mainly because it’s impossible to compare, both come with their own challenges, and in the case of Slave Zero X, those challenges were akin to “the scaffolding being built under our feet as we were walking,” says Scott Brown, in reference to how so much of what they had to do technologically was them inventing the process.

“Barely anything was provided by the engine itself,” adds Bridge, “and the fact that the programming team were fighting to make these things work and to build new, interesting solutions to stuff was kind of very similar to the development environment of the original Slave Zero, or Hagane or any of those old SNES through to PlayStation 1 lavishly animated 2D side-scrollers, that was important to us.”

Not that this is news to any game developer. As Bridge puts it, “Obviously no [game] engine makes a game for you, every engine requires a degree of independent development work and figuring stuff out on your end and adjusting. I doubt there are many games that come out nowadays that are completely ‘off the shelf’ or whatever in terms of tech that’s used in them.”

But that doesn’t mean Slave Zero X wasn’t special with regards to what the team had to do to make it work.

“Everyone will be making their own adjustments in order to make it work. Everyone’s fighting their engine a little bit,” she continued, “but we were in this situation where the culmination of tech that we were using was completely unprecedented. I don’t think anyone has made a game exactly like this before – obviously people have done very similar things.

But in terms of making your maps in TrenchBroom and then exporting them from the Quake level editor into GameMaker, a game engine that doesn’t even really like doing or pretending to do 3D to begin with, and we have these 3D backgrounds and then 2D sprites in the front.

Then also have a complex battle system on top of that. I think, talking about it from the perspective of an art director more than a technical one, because I was not obligated to wrestle with these technical challenges directly, but they very much affected my work because it was stuff like ‘how much detail can I afford to put on this design that has to be worked on by 2D animators’ versus ‘how much detail can go on this design that is going to be done our 3D animator.’

How high-res are our 3D models going to be, how many poly’s are they going to have, what’s the texture resolution going to look like. I think it was about finding a balance between one-to-one communicating the exact vision that I had, or that any of the artists on the team had; we had to find a balance between bringing to life our personal vision and then finding where that sits in this particular look, this era.

I think more often than not what came out of it is kind of like when people put things through VHS filter or something like that. There’s something about putting a lot of special effects on old movies through that blur of the low resolution film and the colour bloom and stuff you get on old film before the era of pinprick digital sharpness, that kind of unifies everything.

If you look at Jurassic Park (1993) now, so many of those effects still look really good in part because they’re kind of unified by that blur that passes over everything. The imperfection of the visual fidelity of the VHS medium binds everything together, and I think for us we had the same thing.

Stuff might look weird, and then we would put it in the game, and in-game with all these other elements going together and seeing characters moving against it, it would really come together.”

Bridge did also admit that finding this necessary balance meant a lot of letting go of elements and ideas her and the rest of the artists might’ve had from the concept stage to being implemented in the game.

Brown goes further to describe that for him and the rest of the Slave Zero X team, they each have a love for trying to write their own versions of game history. Making games as if there ever was a console like the “Dreamcast 2.”

“To me, there’s a lot of dream like charm and appeal to sort of, backtracking and going down evolutionary dead ends with games technology. Everyone that worked on the project it’s because that vibe really worked for them. I think that’s something that motivated us all and got us on the same page.

It’s not exactly nostalgia in the normal sense, but it is sort of pining for ‘what if this trend continued’, ‘what if this sort of technological approach was the way that we kept making games,’ and can we realize them. Internally, we joked sometimes that we’re making a game for the Dreamcast 2. Just this sort of, what if, what did we not try out, because we left that path behind.”

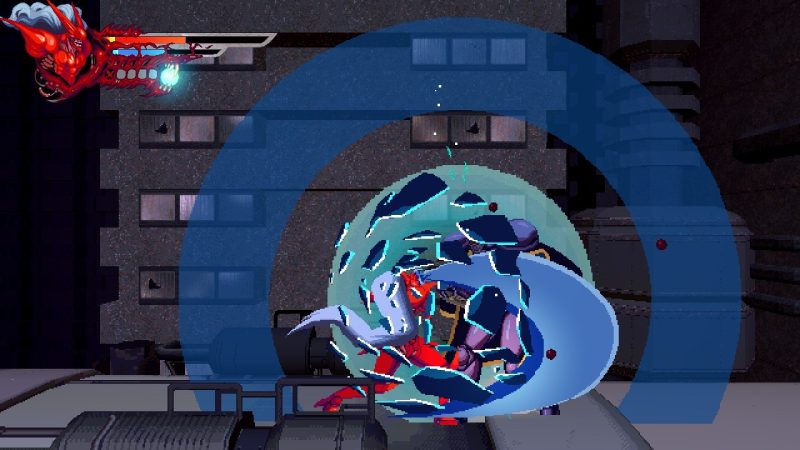

As is always the case though with good artists, working within limitations only generates creativity around how to make the most out of those limits. An example both Brown and Bridge highlighted was the design for one of the game’s bosses, that despite not being what Bridge had originally envisioned, by the end, “it really boiled the design down to what was the most essential elements of it,” says Bridge.

Brown also noted that the changes they made led to more ways of telling the narrative, since their inability to make this particular boss have the weapon they first thought of ended up creating a deeper connection for the character in the game’s world, where his weapon seems like the ultimate version of ones you’ll see grunt troopers use.

“It connects him to all the normal troops that you fight, it sort of makes him the most ostentatious version of who he commands,” says Brown, “in a way that if he had a totally unique sword, that might not have had the same connection. So it’s cool how that worked out even in simplification.

We sort of created something that ended up telling the story in a different way, about how he sees himself, his own standing amongst all the other characters and stuff. It’s cool. That’s my favourite part of the game development process. Dialogue, and not really treating anything as a setback but as an opportunity to come up with what you can mine from that [original idea], that can still contribute, even if its a compromise.

How can we push this compromise to be something interesting that still services the character or the story, or whatever.”

“It’s Not A Throwback Anymore”

In the first two months of 2024, we’ve seen major games that cost millions and millions to make with major studios backing them pale in comparison to the success of much smaller titles. It’s the inevitable result of an unsustainable pace that demanded games get bigger and more expensive all the time.

The game’s industry’s ‘missing middle’ is starting to make a return, and it’s games like Slave Zero X that are entries into that middle ground. Bridge called Slave Zero X a “B” game, on the modern lettering scale, even though in her opinion, she’d actually classify it as a “SSS ranked game.”

It’s clear though that there’s a growing desire for smaller experiences, in part led by retro style games, and both Brown and Bridge see it as the industry gaining back a section of itself that got lost for a few years.

“It’s not just that there’s a rise in an appetite for retro games, specifically, and I think there is a continuing rise and expansion of that audience. But I think especially as segments of the AAA industry continue to escalate further and further into super high fidelity, super high realism, super high asset cost and all these other things, and these games become multi-million dollar affairs that take seven years to develop and then they come out and are these massive cinematic experiences and stuff like that.

I think that’s cool, but I think that what used to be like the B game section of the market, where a lot of different levels of visual fidelity, a lot of different visual styles and stuff could coexist – I think what started out as retro throwbacks, like ‘hey we’re making a game kind of like an old game.’ I think people still use that terminology a lot but I think it’s more just that we’re actually seeing an honest revival of these techniques.

I don’t think that it is a throwback anymore, I think there’s just that segment of the industry that’s making 2D games, that’s making 8 or 16-bit games, people that are making games now in the PSX style, they use ‘throwback’ and ‘retro’ and stuff like that as a shorthand for ‘we’re making a game like those older ones,’ but it really does just feel like the industry is growing that segment of itself back, as the B game section has been completely vacated by the larger bodies, which are all moving off to make much larger games on a much larger scale.

And I think that there’s a big appetite for those [B games] as well because you’re talking about a segment of the market where people can pay a much more reasonable amount for a smaller, more compact, more self-contained experience. Which very often has more of that essential idiosyncrasy and flavour that comes from specific developers and directors and stuff like that, coming through in the game.

Whereas a larger game might have like, 400 people working on it – that’s not to say that interesting work isn’t being done in that sphere either, obviously I’m biased because we’re directing a game that we think occupies that [B game] space. But I think there is an expanding audience for it, because that space didn’t exist for a long time.

The height of it was probably the PS2-era where you had games being made at all sort of levels. I think people are excited to see the fact that a game can come out and be anything these days, and still be a massive success is hugely, hugely important.”

An excellent example of this, Bridge points out, is Lethal Company, a game that doesn’t really have anything to throw back to, but is made in a style that is very much a throwback for older players who’ve been around longer. Even though the development team wasn’t all entirely alive to experience those games the first time around, and as Bridge says, “cut their teeth in Roblox.”

“Retro, throwback, those terms will continue to be used because they’re a good shorthand, but I don’t know if they’re as true anymore, I don’t know if it is just about the throwback, I think it’s also that people want to work in these spaces, with these tools and in these styles because there’s still something to be said and done with them. They weren’t exhausted when we were moving through them the first time.”

It’s almost another retro revival, as Brown describes it, but this time with all the developers who were kids when the first big retro revival push happened, who grew up understanding these games to just be a part of the modern gaming sphere. The ultimate net-positive effect of having remasters and remakes continue to be popular among players, because it helps keeps these styles and these kinds of games alive for a new generation.

“Our team ranges from people in their 40’s and in their 20’s, who were all influenced by the same types of games,” says Brown. “If you caught that retro revival, and you were a kid, that’s just what games were to you.”

Now, Bridge and Brown are those kids grown up, making games in the styles they grew up with, even if those styles were technically already before their time. They’re artists with a huge amount of respect and understanding for what’s come before, looking to find new things in the styles that others have left behind.

Slave Zero X is that expression, and it’s a wonderful example of the kind of amazing, artistic and innovative work being done in games today. Not everyone is trying to make the next big live service that takes your money monthly for the rest of your life.

“More than anything,” says Brown, “I think everyone can appreciate seeing something that they are familiar with, but in a way they haven’t seen before. Chasing those forgotten evolutionary paths is a way to stumble back on those things. That’s where a lot of magic can be found.”

Slave Zero X is now available on PS5 and PS4.

Special thanks to Francine Bridge and Scott Brown for their time and generous answers, and to Jasmine James for her work in making this interview possible.